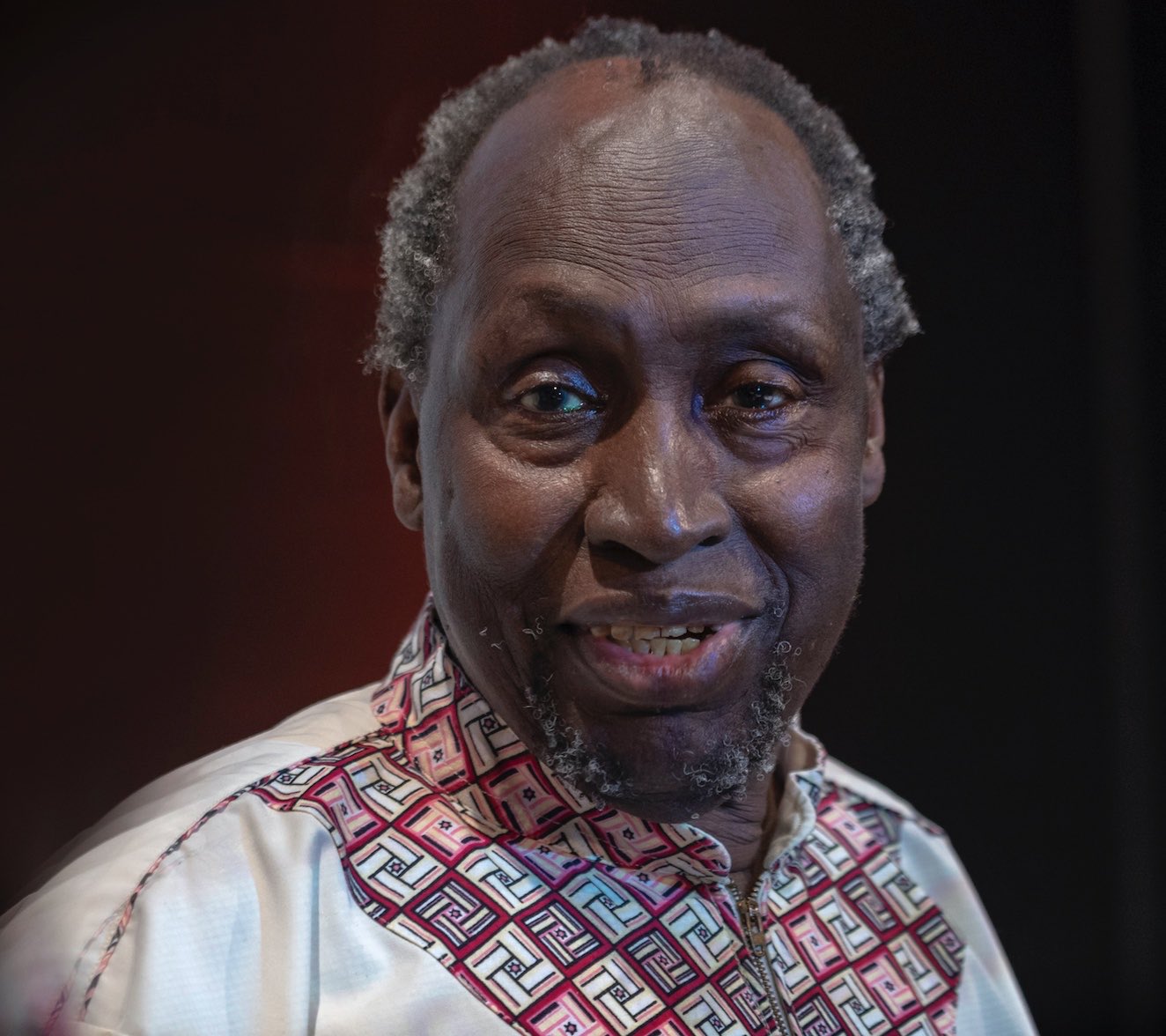

Transcript: 130. Ngugi wa Thiong'o on... Himself!

The great Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o joins us to speak about his career, his influences, and the power and politics of language.

Note: this transcription was produced by automatic voice recognition software. It has been corrected by hand, but may still contain errors. We are very grateful to Tim Wittenborg for his production of the automated transcripts and for the efforts of a team of volunteer listeners who corrected the texts.

Peter Adamson: It is a great pleasure and privilege to have you on the series. You've written a lot and you've written in numerous genres. You've written novels, you've written plays, you've written essays, you've even written film scripts. And so the first thing we wanted to ask is how you see the philosophical aspects of your work as being expressed in different kinds of writing. So do you think of one particular form of writing as being particularly well suited to express philosophical ideas, for example?

Ngugi wa Thiong'o: Well, first question is what's philosophy, right? Is it such a wisdom, right? As I was saying, philosophy is rooted in oratory. At least the Greek philosophy is rooted in oratory, remember. I mean, the dialogues of Plato's dialogues, so Socratic dialogues, everyone more or less begins with somebody's coming from the market. They go by somebody's house. They ask to enter the house. They are welcomed and they sit down. A topic arises about beauty or about God. And there a dialogue begins. So philosophy is rooted in the very ordinary and philosophy is rooted in oratory, okay, in conversation, right? Yes. So I would argue that literature, whether mine or Shakespeare, is actually also has philosophical dimensions as well.

Peter Adamson: And do you think that writing can capture philosophy as well as live conversation?

Ngugi wa Thiong'o: Yeah, again, depends on how we define philosophy. If you search for wisdom, if you're seeing connection between the form of phenomena, if you're asking questions about patriotism or whatever, a lot of literature does ask those questions by implication. So I won't just say just me, you know, but writers like Chinua Achebe before, Things Fall Apart. I've seen the work quoted by philosophers, politicians, religious people, and that kind of thing links fall apart. And I believe some of my books, particularly, I would say the ones which are fiction, like Petals of Blood and Wizard of the Crow, which I wrote in Kikuyu, in my mother tongue, they ask questions about everything, about love, politics, relationships, and so on. It's only they don't use the current language of philosophy, in the sense that they don't use the language of philosophy. I don't mean to be derogatory, but you don't see the jargon of philosophy, but they ask similar questions, and then they explore those.

Peter Adamson: You just mentioned Achebe, and we can say that throughout your works, you refer to a lot of other Africana authors in literature and philosophy. So just to name a few names, C.L.R. James, Frantz Fanon, Eric Williams, Walter Rodney. Actually, you recently wrote a forward for a collection of writings by Walter Rodney, and we were wondering if you wanted to just pick out one or two thinkers who have been particularly influential on you.

Ngugi wa Thiong'o: The question is about development. Very, very important. It's the whole relation between Africa and the West. And the title of his book, actually, is very important, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. It's kind of the very title negates the whole colonial assumptions of having brought development to the continent, of having brought technology or whatever to the continent. They say, no, no, on the contrary, what they brought is under development, how Europe underdeveloped Africa. Right? Frantz Fanon was very influential in African thought, where the professional philosophy or literature or politics. Right? How did Fanon affect me? I can tell you because it's very important to me. I wrote my first two novels, Weep Not, Child and The River Between, before I read Fanon. And then I came to Leeds. I was also a journalist in Kenya for a long time and even wrote a column under colonialism. And I had a column as I see it, which is still a fairly philosophical instance. You see how you see things. Anyway, so I was born in a colonial situation. Kenya was a settler colony. And we saw things in Kenya at the time in terms of black and white oppression or white oppressor, black oppressed. Okay. Everything, black and white explained political reality because you talk about poverty and wealth. White was wealth. Black was poverty. You talk about power. White was power. Black was... Right? So we get independence or rather we regain our independence in 1963 in Kenya, say. Now, questions arise. We see things in terms of black and white. In fact, we're seeing Kenya, Europeans would say Kenya, white islands or white man's country. And we would see, our liberation movement would see Kenya as a black people's country, counter back and explain it and fairly accurately. As a dependence, you see, wait a minute, same things are happening. True, there are now a few rich Africans, but the majority are in the same situation. How do you explain this? You can't explain it purely in terms of black and white. And it doesn't give you the answers. And it's Fanon who opened my eyes. It's where the Wretched of the Earth... for also national consciousness. I have to explain. I have to see this not so much in black and white, but in social terms, class terms, that's a working class and a middle class and that kind of thing, an imperialism. And that helped me to shift my writing thereafter, you know, but I'm actually to write my Grain of Wheat, I read Fanon or Petals of Blood. So Fanon really influenced me a lot. He was a thinker, philosopher. Yes, actually.

Peter Adamson: That's really interesting. Sort of tempted to ask you more about Fanon...

Ngugi wa Thiong'o: He influenced many people. Really, he was a book writer that has been very impactful. Tsitsi Dangarembga, you had the title of her book, Nervous Conditions, it's taken directly from Fanon. The very title of the novel is from Fanon.

Peter Adamson: Well, I should ask you something about your own writings. And maybe I'll start with something that you just mentioned a few minutes ago, which is the decision you made to write in Kikuyu. And this is something that obviously is a political choice. So you're pushing back against the dominance of English as a world language, a language that was spread by colonialism. Can you tell us about that decision and maybe talk more about why you decided to start writing in your native language?

Ngugi wa Thiong'o: Yeah, talking of course, books, philosophy, I would put, you put probably the color in your mind, as a philosophical work. In the book I wrote in 1964, and there were a series of lectures I gave in Auckland University in honor of their first chancellor, Rob. They called him Rob and Lectures. I was asked to speak on the question of language, African literature, or something like that. And these are books which became The Colonized Mind. And these are some of the thoughts I had when I was imprisoned in Kenya, committed maximum security prison as a result of, or because of, a play, Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), which we wrote in Kikuyu, my mother tongue, and it was performed by literally small farmers and working people, factory workers, plantation workers. And it was stopped by the Kenyan government in 1977, November, December, the same year I was put in committed maximum security prison. So when there, I started asking myself, why? Why would the Kenyan government, an African government, put me in prison for writing in an African language? It's a very painful question. Why? It doesn't make sense to me. Why? Because I've written other plays in English, which are as critical of the government or the post-colonial conditions in Kenya. And really, I was never put in prison beyond police questioning here and there. That's when I really started thinking about the language question seriously. And I look at it this way. In all colonial conditions, or in all conditions of the oppressor or oppressed, language has always been used as a means for fulfilling the desires of oppression. And I've got good examples of this: Let me start with Africa. We, the children, were often given corporal punishment, beaten even, or humiliated in every possible way. When you are caught speaking mother tongue in a school compound. Really. But then I found the same thing happened, let's start with Wales. Welsh kids were humiliated the same way. They carried something called Welsh knot. If you are caught speaking Welsh in a school compound. It happened in Ireland. It happened about Native Americans. It happened about Native Americans who were humiliated in every possible way. They were given European names, languages. It happened in New Zealand, Maori. They were beaten, you were beaten in the same way. All over, the same story. French colonies, the same pattern, punished people for their mother tongues, but glorified them in a form when they speak the colonial language as well. Why is that? The question arises. If I know my mother tongue and add English to it, or French, what's wrong with that? I'm more powerful. I know my mother tongue, but I also add English to it. I know my mother tongue, but I also add English to it, or French. But the colonial education wasn't like that. It was a negation of African languages. It was built on negation. The knowledge of English was built on a negation of African languages. Everywhere. A negation of Maori languages, Native American languages, Native Canadian languages, Native Australasian languages. Now, compare this. If an Englishman goes to France to study French, they don't punish him for his English. They'll teach him French to add to the English he has. On the other way around, a Frenchman can go to Oxford to study English. That's normal. So the colonial situation was abnormal. It had to do with colonialism of the mind, tying, making a bond between the colonized and the language of the colonizer. They see themselves as outsiders. They associate the language with non-development, with humiliation, with negativity. So you create a class, an elite, a European language-speaking elite, ruling a country of African language speakers. This is what I call colonizing the mind. And so I wrote a book called Colonizing the Mind. Unfortunately, the situation has been normalized now in independent Africa. In Africa, I call it normalized abnormality. Right? Normal abnormality of the colonial system. Because even at that time, it was abnormal to make a child, to humiliate a child for mother tongue. And so adding to that language so they know many languages. No. You had to make them deny their languages in order to master the languages. Continue with that abnormality, which is now normalized. So what we have in the post-colonial situation in Africa in most places is normalized abnormality. And that question of normal abnormality has not been addressed all over the world. No, not yet. Shall I give an example of normalized abnormality?

Peter Adamson: Yeah, absolutely. Please.

Ngugi wa Thiong'o: Okay. Let me give an example. And I'll begin with here where I got refuge in America. And I'm very grateful. I got refuge here. I got a job here. As you say, I'm a distinguished professor of comparative literature and English. I had three professorships in New York University for 10 years. Professor of studies, comparative literature, and another one on languages, honorary one. Now, in essence, I was forced out of my own country. I'm grateful that I got an opportunity here. At the same time, this doesn't make me feel from asking myself, what is America? The one which intrigues me a lot is the question of American independence. And I ask, what is American independence? What's Canadian independence? What's New Zealand independence? Aren't there colonizers here? Yeah. America was a separate colony. Some people from Europe came to America and colonized people who owned America, what we call Native Americans. So decolonization would mean that the people who were colonized now become free. But no, it's a settler community, it's a colonizing community who declared themselves independent. So you can see that America is a normalized abnormality. The same with Canada, the same with Australia, New Zealand, normalized abnormality because Native Americans have never gone through not being colonized. They never went through the process, that process, or Native Canadians, or Native New Zealanders, or Australians. Kenya, I'm very proud of Kenya, because Kenya was a settler colony, but it was the first to defy that trend which had been there of settler colonies declaring themselves independent, meaning they continue to colonize the people. They normalized the colonization. So to be very frank, we live in a world of normalized, rooted in normal abnormality. And many things in the world going on today, wars in Iran, Kilo-Kaddafi, other things like that, are really Afghanistan for 20 years, Vietnam, I mean, and other wars. You can see they are rooted on the assumptions, but it's a normalized abnormality that's ruling the world, right?

Peter Adamson: I'll ask you kind of a small question, but something that Chike and I were curious about is that in Decolonizing the Mind, the book you just mentioned, you actually talk about writing in Kikuyu, but also in Swahili. And you've written quite a lot in Kikuyu, but have you thought about writing more in Swahili as well?

Ngugi wa Thiong'o: No, no, no, no. My Swahili is not very good, but I really would like, but the fundamental question is, you know, Swahili is generally an African language, like Kikuyu, like any other African language. But it is this other dimension, that's a language that is known by many other communities. Swahili is an African language, which also happens to be widely known in Kenya, in Tanzania, in Uganda, in Congo, that kind of thing. It's a very good language for linking and enabling conversation among African languages. African language as a whole, in Kikuyu, Swahili, needs to develop. We can base all the language on the knowledge of our mother tongues, whatever it is, all over the world. I don't believe in this nonsense they have, that you must have one. You can have a national language which enables conversation among the different language communities, but that should not be negation of their mother tongues. The history, the philosophy, millions of years of thought that they have gone through to make that language. And at a stroke of a pen, you say it doesn't exist. It's the same as ban libraries. You say, you go to ban libraries, you say, oh, don't do that, it's horrible. But it's exactly the same thing when you suppress the other languages. And I don't believe in the hierarchy of languages. I do all language should have equal give and take on this equality, like conversation among languages. But there's nothing wrong if you know another language that enables you to talk across those other languages. This is where I put it, and I repeated here. If you know all the languages of the world, and I mean all, and you don't know your mother tongue or the language via culture, that's enslavement. But if you know your mother tongue or the language via culture and add to it all the languages of the world, that's empowerment. In other words, English is a very good language, so it's fine. But so also is Mandarin and Russian. But so also is Zulu, Yoruba, Kikuyo, Ludo, Swahili. So what would, even if you have an African language spoken across the continent, it should not be on a hierarchical basis. It should not be built on the negation of the other languages. But it can be used. It's very useful. It's very important that I can go to Tanzania and speak Swahili, or other parts of Kenya and speak Swahili. But I'm going to get, so when I come to America, I can speak English. I went to Japan once, and I couldn't follow any, I mean, the first time I went to Japan, and I don't have any Japanese with me. So whenever I had an English person speak, whoever it is, I would gravitate towards them. Yeah. What's wrong in language is a hierarchy of languages, not language per se.

Peter Adamson: I think what you were just saying leads to an issue that we noticed in your writing as well. So something that we've talked about a lot in the podcast is it seems like there's this tension between thinkers who want to celebrate a particular culture or maybe a particular language, and think about philosophical ideas that could perhaps only be expressed within that particular culture. And then the idea that philosophy should be getting at universal values or universal truths. But it seems like you're saying that you sort of start from a particular place, and then you, through this conversation with other peoples, you get to something universal.

Ngugi wa Thiong'o: Universality comes from particularlity. Universality is an abstraction, it's rooted in particularity, but the universal is inherent in the particular. Okay, we are all human beings, you and I. But I'm black, you are white. That's particular of you, a particular of me. But the human is a universal. Whether you come from China or wherever. But that humanity is not expressed in an abstract universality, it's expressed in particularity. Of Ngugi, Kikuyu-speaker, Achebe, Igbo-speaker, Shakespeare, English-speaker, and so on.

Peter Adamson: You're interested in James Baldwin and Shakespeare, right? Because you mentioned that in this other book you wrote called Global Lectics, you talk about James Baldwin and Shakespeare when you're explaining the title, isn't that right?

Ngugi wa Thiong'o: Yeah. I like their works a lot. In fact, you know, the irony is that in a way, the moment I embraced and called my mother tongue, I came to appreciate Shakespeare more because I could see what he was going through. Or with the French writer Rabelais, because I could see how they were discovering their languages. You know, English was emerging from Latin domination, and so was French, many Western languages. They were emerging out of Latin hegemony previously. So many of the writers, including Dante, the examples you seem to have, and the originality comes from the discovery of their languages anew. So you can see them, very widely. He's very widely in some cases because he's enjoying seeing how he can say these things in English in this way and that way. The same with Rabelais, all of them, they play with their languages, which they have discovered the newest, beauties, possibilities.

Peter Adamson: So actually, let me ask you a question about that as well, because so you're a writer of fiction, you've written literature. Rabelais, Shakespeare, great writers of literature. And on the other hand, you're also someone who's very interested in political issues. And you clearly believe in the power of culture, like literature and political life, not just literature, but culture in general. So at some point you say that culture is not like an accidental growth, it's not like a sixth finger, but it's more like the flower of a plant, which is something I like a lot. Yeah, I like that a lot. So can you say something more about that, like the sort of the power of culture to change things?

Ngugi wa Thiong'o: I look at a tree or a plant. When you see a plant, we admire its beauty. I mean, and the beauty we admire really is actually the flower, it expresses the beauty of a tree, more or less. You know, that's all right. But then you look at it carefully and you say the flower, that's not just image. It's part of the tree growing or a plant, then it gives flowers, beautiful. The flower expresses the totality, the being of that tree. But it's so important, because the flower carries the seeds, the future of that tree, that plant. So I compare culture to that kind of flower in a sense, it arises from the totality of the being of that community. But it carries the seeds of the tomorrow of that community, the memory, if you like. So for me, it's something which is static, and more than a flower is static, because the flower carries the past and the future of that plant, isn't it? Because it is a result of the past of that community, from the seed, the growing and then flower. But then, same flower, beautiful, wonderful, it has a seed for tomorrow. If you apply for a new flower and no seeds for tomorrow, we'll feel a little bit of suspicion, we know what kind of plant is that one.

Peter Adamson: And what would you say to someone who's skeptical about the power of something like a novel or a play to change political life?

Ngugi wa Thiong'o: No, the novel, in general, just put the arts in general, which link art to the imagination. And the human is impossible without imagination. What's a human being without imagination? Then he's like, suppose a lion or whatever, you will not be friend than any other animals of nature. But imagination is the one thing, because in imagination, we can build pictures of tomorrow. Look at architects, for example, they imagine a house in the head, they see it, and then they build it. We imagine things, and then realize them. So imagination is one of the possibilities. And what the books do and the arts, they produce all that imagination, but they also feed that imagination. That's why in all communities, children are brought up with stories of all the impossible beings, of angels with wings, of God, you imagine them. And then sometimes you have to realize them in fact. What is that enriches that imagination? It's the arts, stories, you know, novels, and then you enrich the imagination. But that imagination is the one which enables discoveries, inventions, also possibilities we have. We have the human. So the arts are not something which is secondary to our being, it's central to our being. And I suspect one of the reasons why many totalitarian regimes go for the arts is to limit the imagination. And you can see this is happening in America. Now they are banning books in America. Certain books are not allowed in America. That's why they talk about Black history. They talk about slavery. At least in Florida, America. What's that mean? They are functioning in the same way as all totalitarian regimes do. And they do it to limit imagination because they never see the possible worlds. We see different worlds, alternative worlds. That's how human society has developed. And the arts are part of that imagination. Okay, they are products of imagination. But they are also, to put it very simply, the food that nourishes the imagination of the people. Just the body needs food. We eat food, function physically. Imagination needs the arts. But then, why is it the same pattern all over the world that totalitarian regimes go for the arts? The imprisoned writers all over history. Writers, artists, of imprisonment or exile. Why? What they call in the Bible, the biblical prophets were writers, but they spoke other words. They had visions. Ezekiel, the valley of bones, bring their life to the bones and all that. Today we call them writers only if they don't try to spoke their words, their visions. They could see dangers ahead or other possibilities and they spoke them. Revelations also of the end. But what they're doing in Florida, in America, you cannot believe it. They are banning books. I mean, how is it? And they don't continue with the history of totalitarianism and books. And they are doing the same thing once.

Peter Adamson: It actually brings me to the last thing I wanted to ask you because, I mean, obviously you've been around for a while and you've worked in American universities and your works are on reading lists at universities in America and all over the world. Do you have an optimistic attitude about the way things are going? I mean, people talk about decolonialization all the time now, or decolonizing the curriculum, for example, at universities. Do you see a lot of progress being made or?

Ngugi wa Thiong'o: I think it's good. Life is terrible. No matter how we look at it, to walk, walking alone is a struggle between stopping and moving forward. One leg has to be anchored to the ground stationary to allow the other leg to go forward. Then the other one stops and because it stops, the other leg can move forward. Imagine a world which was completely oiled so that the other leg could move forward. They're oiled so that the other leg can move. You can't move. Movement is always a struggle. I mean, this has been said by Hegel and others. I'm not saying for the first time. It's a struggle of opposites, darkness and light. Everything is a struggle. Growth itself, you and I, we've been talking for the last two minutes or half an hour. Are we the same people who we started talking into ourselves in our body? Some have been dying and others have been born. Blood has been circulating through our... went over high blood pressure is when the blood moves harder. But it means there's a struggle going on in our bodies, in our cells, in the way we walk. I mean, the struggle is always there. And there's no human without struggle. When we don't struggle, we die. Right? Isn't it?

Peter Adamson: So maybe it's not so important how things are going. The main thing is to keep moving in the right direction.

Ngugi wa Thiong'o: Yeah, we struggle. There's always even no matter how good it is, there's always trouble between the one who looks for forces that's creating a tomorrow and for the people that are pulling us backwards. And that's how it has to be there. It is there. Even today, it's there in America. You can see it is there in Kenya, it's there in Russia, in China, in India. The struggle between today and force for tomorrow.

Comments

Add new comment