21 - We Don't Need No Education: Plato's Meno

Posted on

Peter tackles one of Plato's most frequently read dialogues, the "Meno," and the theory that what seems to be learning is in fact recollection.

Themes:

Further Reading

H. Benson, ‘The Priority of Definition and the Socratic Elenchus,’ Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 8 (1990), 19-65.

G. Fine, ‘Inquiry in the Meno,’ in R. Kraut, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Plato

(Cambridge: 1992).

D. Scott, Plato’s Meno (Cambridge: 2006).

Comments

Alternate title

Honorable mention goes to a title suggested by a student of mine: "Finding Meno".

In reply to Alternate title by Peter Adamson

Duly honoured!

Duly honoured!

Meno's paradox

Hi Peter,

upon my first listening I felt that you hadn't given sufficient time to your explanation of Meno's Paradox to allow me to appreciate the basic truth that it contained, i.e. there is a problem in explaining how we can learn.

However, after 2.5 listenings of the podcast, I am of the opinion that the paradox is nonsense and that coming by knowledge is easy.

For example, let us assume that as a youth you saw Buster Keaton on TV one afternoon and were enthralled. Subsequently, you watched him each afternoon when returning from school and furthermore went to the library and borrowed a biography of Keaton as well as a history of silent movies which you read with enthusiasm.

You have therefore gone from complete ignorance of Keaton, through awareness, to knowledge and in the process you will no doubt have heard mention of Harold Lloyd who, as any fule kno, was the greatest silent movie actor of all. :-)

Thus, since the paradox does not exist, both Plato's solution and his willingness to offer a solution where none is required, do him no credit.

No doubt this is simplistic and wrong. But why?

In reply to Meno's paradox by Felix

Meno's paradox

That's a very good question. One issue that arises here I guess is what sorts of knowledge Plato has in mind; that's something I discuss in a forthcoming episode, an interview with MM McCabe. But more generally, remember that this is a paradox about inquiry, so the "starting point" he's thinking of would (I guess) be something more like this: I set out to discover about Buster Keaton but know nothing about the topic, not even that Buster Keaton is a person.

Of course you might reply that not all knowledge comes from inquiry, sometimes we just come across new information/knowledge (this is implied by your imagined situation where I am lucky enough to come across him on TV). This brings us to the question of whether new experience can give rise to knowledge. Plato seems to think not: he argues for this in the Phaedo which will be the topic in episode 24.

Perhaps the main thing to realize (again, this is something that will be discussed in future episodes) is that Plato thinks of knowledge as a very high-level attainment, and that helps to explain why we can't acquire it casually, as it were.

Does that help?

In reply to Meno's paradox by Peter Adamson

Meno's paradox

I shall listen to the forthcoming episodes and then reconsider my position.

Thanks

In reply to Meno's paradox by Peter Adamson

knowledge of...?

Let's forget a specific person, and take a concept such as 'music'. If you hear Bach, Barry, Beatles and people tell you that is music, then you may have a good, if narrow, definition of what music is. Can this be knowledge? Now you hear be-bop, Cage, Varese, rap. Does this fit in your previous definition of music? What about a police siren? Or birdsong? Or me whistling in the bath? Is there a definition that takes in all these, or takes in some and excludes others? One's experience of Herb Alpert hasn't prepared you for a definition that includes Tibetan throat singing.

So experience can only get us so far.

Now try doing the same thing with 'friendship', or 'humour', or 'justice'. If your inquiry took place in a school playground, your definition of justice would probably based on 'might is right'.

To me, this is what Plato could be implying when he says knowledge is recollection. 'Justice' (along with Music and Pity and...) are all timeless concepts which are known and exist beyond specific examples or experiences of scapegoating, or family vendettas which pass for Justice (and may indeed be Justice for all I know - I know my limits!!).

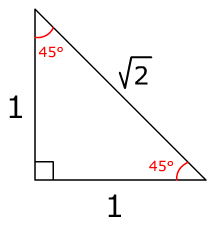

The example of recollected knowledge used by Socrates in the Meno is, of course, a mathematical one. Why? - because Mathematical methods work in all cultures, and in all languages, because they are shared concepts which exist outside of a specific time. Surely this is a clue to the way Plato wanted us to think about these other concepts.

And does this fit in with the theory of Forms? It is easy to see how abstract concepts (as opposed to physical objects) can be imagined in this way.

OK, I've probably gone down a blind alley,,,

Meno's Paradox

Hi,

Loving the podcast so far, especially the presocratics, recommended it to several friends.

Your comment here brings me to a long standing gripe I have with undergrad degrees.

When I did my undergrad we of course got Meno's Paradox and Forms as the main Plato components along with a few others such as the Republic. That was in the intro to philosophy 1st year not the specialist module on him.

What I've always wondered is why lecturers choose these parts of Plato as usually not just the first of Plato you learn, but the first philosophy you learn. When I taught Philosophy A-Level, sure enough first chapter of the book was Plato's Forms, I skipped it.

Plato said a lot of great stuff but stuff I never got to hear this at undergrad level because once I heard Meno's Paradox and Forms I thought what a load on nonsense, thought Plato was ridiculous and moved on to much more sober philosophers. Now much wiser about Plato I wonder if there could be perhaps better choices made about what to teach of his. You yourself on this podcast start with Socrates, then the Euphedemus, great choices, but then mention on this particular podcast you start your undergrad students on Meno's Paradox.

In reply to Meno's Paradox by Paul

Introducing Greek philosophy

Hi Paul -- Well, I do teach Meno's paradox but I don't actually start with it, I start with some Socrates and do either Apology or Euthyphro. More importantly, though, I do the Meno without yet mentioning Forms (so much as I do on the podcast I actually emphasize that you can understand a good deal of what Plato is up to without invoking Forms). That course at King's is an introduction to Greek philosophy, though, not to philosophy or history of philosophy in general, and it's only 10 weeks so we do get to Forms pretty fast!

A different reading of the Solution to the Paradox?

Hi Peter,

More often than not, with your podcast not being an exception, Recollection theory is cited as the solution to Meno's paradox which is then demonstrated with the slave boy. Whilst it does seem Recollection theory explains how we can inquire into that which we know absolutely nothing about, (as we already knew it before), I was wondering what you make of the idea that actually it is the questioning of the slave boy which does most of the work.

So the situation is that we can't inquire into something we have no knowledge of. The slave boy has no prior knowledge of geometry and so shouldn't be able to inquire into it. Yet he is able to arrive at the correct answer without being taught. So inquiry is possible with no knowledge, because true beliefs about something are enough to enable inquiry to begin. (The slave boy had no knowledge of geometry, but manny beliefs about them; some true and others false.) This reading seems equally effective at refuting the paradox, and doesn't rely on a contentious story about souls. Socrates clearly thinks that through inquiry rational people will make progress in the right direction, disregarding false beliefs and keeping hold of the true ones. So the elenctic method disarms the paradox, and Recollection theory justifies our tendency to recognise our true beliefs?

I read these ideas in 'Gail Fine: Inquiry in the Meno' and was interested in your thoughts.

In reply to A different reading of the Solution to the Paradox? by Edward

True Belief as a solution

Yes, that's a very good presentation of the Fine solution, I think. One problem that immediately arises is coordinating the Meno story with the Phaedo, which seems to put beyond doubt that Plato took the recollection idea to relate to contentious claims about souls (in that dialogue, these claims are the whole point). But leaving that aside, I tend to think that even within the Meno there is a problem with the idea that true beliefs are enough: this is that Plato is worried precisely about how we can get to something as strong as knowledge, and he would I think be just as worried about how to get there from true belief as from ignorance. The problem is how we get derive knowledge from a situation where there is as yet no knowledge. If we take that as the problem Fine's solution doesn't really help. I like Dominic Scott on this, see his book on the Meno which came out a few years ago.

Peter

Interchangeable roles?

I wonder what would happen in the Ménon, if the slave had led Socrates through the geommetrical dialogue and not the other way around...

In reply to Interchangeable roles? by Luisa Costa Gomes

Switching roles

I would say this question opens up numerous interesting issues. Most notably, Socrates must presumably be in possession of some kind of understanding (superior to that of the slave boy) that puts him in a position to ask the questions that will help them advance. So plausibly they couldn't, as you suggest, switch roles and still succeed. You might wonder whether one needs to know about a topic oneself, in order to lead a successful Socratic inquiry into that topic. But Socrates repeatedly says he does _not_ know himself about the topics he is interested in (virtue, etc.). This is a disanalogy with the math case, where he presumably knows the right answer that the slave boy will reach before they start talking; if this is a necessary condition for productive elenchus, then we have a problem. Plato was very interested in this problem, I think, and thought hard about the conditions that would need to be fulfilled in order for Socratic elenchus to succeed (this may be why he shows Socrates talking to characters we know became bad apples later on).

In reply to Switching roles by Peter Adamson

ongoing investigation

What I think is too often forgotten is that Socrates is leading an ongoing investigation. And the "systemic" difficulties of the Parmenides and other aporetic dialogues are as necessary as the Republic, bumps on the way. In the Meno what we tackle is that moral questions are different from geommetrical questions. The differences being submitted to an ongoing investigation...By switching roles in the Meno we would probably fall back into the Paradoxe of Enquiry (that frightens and appalls common sense and philosophers alike)...you have to know something to know at least how to become conscious of what you know, but if you actually don´t know it, you just don´t know where to start, unless you are led by someone who at least has a general knowledge of what it is to know (what is the meaning of "knowing").

In reply to ongoing investigation by Luisa Costa Gomes

inquiry

Yes, exactly. Indeed the slave boy scene could be (and has been taken to be) a depiction of the idea that, recollection or no recollection, the possibility of knowledge depends on finding someone else who already knows what you want to know. Thus if we did not have Socrates to lead the discussion we would, as you say, be back in the initial position of total ignorance envisioned in the paradox.

True Belief vs True Knowledge

Hi Peter,

Just wanted to say that I'm loving your podcast so far. Can't wait to hear about Saint Augustine and Spinoza as well as the later dudes like Kant and Schopenhauer and all those cool cats.

I know this episode is probably far from your mind now as you are working on the medieval era, but I wanted to ask - partly because I think in my asking I might reveal the answer for myself, and partly because I have no True Knowledge - if you could define True Belief and compare it to True Knowledge.

Perhaps you touch on it more in later episodes, but I was confused slightly by the idea of True Belief, specifically in relation to your allagorical reference to betting on the horses.

Is true belief simply a belief that turns out to be true? If so, how did that belief originate? Is it coincidental that the belief is in the end true? There's a 50/50 chance, sort of, for every belief you hold to be true, so surely some of your beliefs will end up being correct -- does that make them True Beliefs?

Or is True Belief based off of something? With the horses, for example, you could have the true belief (a very reliable source has conferred with you) that Horse 5 is going to win, but because it hasn't happened yet it cannot be knowledge. You can only be certain in your belief that it will win, but the outcome is still undecided to a degree.

With this in mind, could it be that all knowledge is simply Belief? We can be certain that we see X, and that X means Y, because we've seen X result in Y, but to take from Descartes (who I'm also super keen to hear about) we cannot really know if it is True.

I'm capitalising 'True' because somehow I see 'Truth' in this sense as being some kind of higher thing, some definitey beyond human conception. Perhaps I'm getting away from myself here, and I feel that I am haha.

Sorry if this is all muddled up. I'm sure there's a few logical falacies in here, and a few dead ends...if you could clear up my concerns how ever I'd be super grateful.

I'll keep thinking on it anyways.

Thanks again for all your fantastic work. I really hope you see this ambitious and remarkable through to its fruition!

Elliot

In reply to True Belief vs True Knowledge by Elliot

Belief and knowledge

This issue comes up a LOT in the rest of the series so you will have plenty of opportunities to revisit it. The general view, in Plato, Aristotle and many who are influenced by them, is that true belief is mere commitment or assent to a proposition that happens to be true. But that says nothing about how one came to believe it (maybe someone you trust told you, maybe you guessed, whatever). Knowledge by contrast is certain i.e. in some sense guaranteed to be true. There is to this day debate about the nature of the "guarantee" involved there: in particular, it is not clear whether the person who knows needs to know that they have a guarantee, or whether it is enough that it is "externally" or objectively guaranteed. An example: suppose you do a complicated mathematical proof. An externalist could say that if the proof is sound and valid, then you do now know the conclusion, even if you yourself would admit that you may have made a mistake somewhere. Others would insist that you subjectively need to be certain that you didn't make a mistake. Ancient and medieval thinkers tend to mix together these two kinds of certainty, the objective certainty of having figured something out in the right way as opposed to feeling or being aware that you are definitely right. Does that help?

Of course whatever it is that would turn true belief into knowledge, it is a further open question whether it is ever possible for us to pull off this trick. Maybe what we need is something that confers absolute certainty, and this is in practice never obtainable for us; in that case we would have your scenario where knowledge is impossible and true belief is the best we can do. But hardly any philosophers go this way with some exceptions e.g. the ancient skeptics.

In reply to Belief and knowledge by Peter Adamson

Hi Peter,Thanks heaps for the

Hi Peter,

Thanks heaps for the speedy response.

I'm onto it now, I think. If I could rephrase it to see if it works I would say: True belief is any belief that is found to be true independent of any methods of obtaining certainty, whereas knowledge only arises once the certainty of its truth has been verified. Does that sound about right?

Thanks again Peter,

Much love from Australia,

Elliot

In reply to Hi Peter,Thanks heaps for the by Elliot

Belief vs knowledge

Right, that's basically it. Believing something is just taking it to be true - it may in fact be true or not. One thing that definitely separates knowledge from belief is that knowledge is only of what is true (you can't know, and at the same time be wrong). The difficulty is that as Plato pointed out, _true_ belief is not the same as knowledge either. So a natural thought is that true belief plus something else (a guarantee of some kind) is knowledge. The history of epistemology is in large part an attempt to say what that additional bit might be!

In reply to Hi Peter,Thanks heaps for the by Elliot

Belief and Knowledge

I'm very late but I just started the podcasts and I couldn't help myself giving in my two cents although this might be wrong but I'll still share what I think is the difference between true knowledge and true belief and would love to hear you thoughts. :)

I in my humble opinion think that Belief and Knowledge stem for the same root (which in my opinion is innate). Why? And this might be a really mediocre example but I'll see if I can get my point across. When a child is born and introduced to his mother, he shows no hesitation in accepting the fact that she's my mother rather not only accepts but acts as if hes not alien to this relationship. Like nobody has to teach a child how to be a child to your mother. So you can say he has some kind of innate knowledge of this relationship.

However, for a child to know how to behave fully well/ excellent moral behaviour with his mother would need knowledge from the external. (I'f you're a religious person, you'd say this is where the role of revelation comes in). Now you BELIEVE that this is what you should be doing to have a perfect child mother relationship. So your belief fortified your knowledge (through results of believing of course).

If I don't 'know' what a mother is how can I possibly believe in anything regarding it?

So I think both are correlated. We wouldnt gain the knowledge of something we don't believe. Similarly we can't believe something we have no knowledge of.

Thoughts are appreciated and welcomed :)

Plato & innatism

You are very cautious about seeing Plato as an innatist like Chomsky, as you say we shouldn't divorce the theory of recollection from Plato's other views about the immortality of the soul, something that many modern innatists wouldn't accept. Yet I wonder if this actually provides further support to seeing him as an innatist. For Plato, we recollect because our soul persists and so we can recall things that were acquired (somehow) before we were actually born. On the other hand, the very fact that we do seem to have such innate knowledge seems to suggest immortality: if we didn't learn these ideas in the life we have now, they must come from some form of previous life. Perhaps an innatist, like Steven Pinker for example, might say that Plato is on the right track here, but that deducing the presence of a soul is not the right conclusion. For Pinker, "instincts" (rather than ideas), such as linguistic ability or humans' widespread and well-founded fear of snakes or heights, come from our genes, which are passed from generation to generation, i.e. a life previous to ours. So, it's possible to see strong parallels between the relationship between recollection and immortality of the soul, on the one hand, and inherited traits (such as linguistic ability) and genes (which can persist over many millions of years, even if they aren't immortal). It seems to me that Plato saw that certain things we can do seem to be given, rather than learnt - even if it's only our ability to reason. Without Mendel & Darwin, positing the existence of an immortal soul as the reason for this to be present within us seems reasonable. I certainly don't think that Plato in any way pre-empted the science of genetics, but he did recognise a feature of human nature (that we're not a blank slate, that we seem to be able to reason mathematically or otherwise without explicit instruction) and realized that this implies, or at least, provides support, to the view that something of us both precedes and persists after our lives. There must be something a priori to start us off, but how did we get it? Plato's mistake is to conceive of the wrong vehicle for this, but it's an achievement just to see that a vehicle is required. Don't you think? It's worth noting that an alternative title that Richard Dawkins considered for his book, The Selfish Gene, was The Immortal Gene.

In reply to Plato & innatism by Greg Hunt

Innatism

Thanks for your comment! Yes, I think that what you are saying here makes sense. If I remember rightly though, what I was trying to argue against in this episode was interpretations that take the recollection theory to be (in Plato's own mind) just a symbolic or figurative way of expressing innatism - so on that view Plato wouldn't be making an unwarranted inference, as you suggest, but actually dressing up a view like modern innatism in mythical language. And what I wanted to say is that this is unlikely since he draws metaphysical consequences from it in the Phaedo.

Knowledge of Knowledge

Thank you.

Naturality of virtue

Hey, Peter!

Let me first thank you for your work on this amazing podcast. Can't recommend it enough.

I'm a little puzzled on the question of the naturality of virtue. If Socrates admits that virtue is a kind of knowledge, and, as we saw, the slave boy turns out to have innate knowledge on matters of geometry (since he doesn't actually learn, but in fact recollects things his soul - which he was born with - already knew), shouldn't this mean that virtue is innate as well? Or does virtue relate to a different kind of knowledge entirely? For example, we might not say that a shoemaker is virtuous as a consequence of his knowledge on shoe-making, right? What am I missing here?

Thanks in advance!

In reply to Naturality of virtue by John

Is virtue innate?

That's a great point: if knowledge is innate and virtue is a kind of knowledge, then virtue is innate too. The only thing though is that if virtue is innate in that sense, and in the Meno and Phaedo it would indeed seem to be, nonetheless it is inaccessible or tacit until we go through a process of philosophical discovery and are "reminded" of this knowledge. So in a way your question just brings us back around to the main point Plato wants to make which is that it is through philosophy that one becomes virtuous and thus happy; but that is a process of being reminded, not a process of finding something out for the first time.

Meno's paradox

Hi Peter!

Firstly, thank you for that amazing lesson!

Secondly, are there any naturalistic solutions to the paradox of inquiry?

Thanks in advance!

In reply to Meno's paradox by Just a skeptic

Solutions

So you mean a solution that doesn't require, say, preexisting souls? Yes, there are various forms of naturalist innateness (so think for instance of linguistic theories that the brain has innate grammatical structure through evolution - something along those lines). Also one idea could be that you don't actually need knowledge to get going but only true beliefs, which should be easier to come up with... and then somehow you go from the true beliefs to knowledge. Actually Plato is operating with something like that idea in the Meno itself and for some intepreters it is a mystery why he himself didn't come up with a more naturalist epistemology rather than depending on the claims about soul.

Socrates begs the question

Hi Peter,

Enjoying the podcast (and the books) a lot.

I'm revisiting the subject of knowledge. For not only do I have trouble remembering what my soul already knows, once reminded I tend to forget again. Alas, memory is fallible.

Which suggests to me a twofold problem with the claim that learning is a matter of remembering.

To recap: Socrates's solution to the supposed paradox is that during endless time our souls learned all that there is to know, so that all we have to do now is start remembering the good stuff.

Two questions, then.

First, how did our souls manage to learn all that stuff? Why, at some point during endless time, didn't our souls bump up against the paradox? Surely, Socrates isn't going to say that our souls remembered stuff that they learned before endless time. Not only does that introduce a rather incoherent concept of time (or, perhaps, an infinite regression?), it simply begs the question.

Second, how do we know when our memories are accurate? How do we distinguish inaccurate recollections from accurate ones? We obviously can't learn how to do it, because the paradox tells us that learning, as such, is impossible. And saying that we remember how to do it again begs the question.

In reply to Socrates begs the question by Bob S

Recollection

Good questions! The first one is actually a point that is often made about the passage on recollection; in fact it almost looks like Plato has gone out of his way to make sure we notice the difficulty because he says that the soul "learned" these things before coming into the body. I can't just tell you the answer here - you'd get different views from different interpreters - but for what it's worth I think the point must be that you can come to know the Forms by something like direct acquaintance when outside the body. When in the body, you only have sensation to work with, and then the problems that prevent learning kick in (e.g. you never see a Form instantiated without being together with its opposite).

The second question might be easier to handle, at least if we assume that what is being "known" here is just the Form, or the nature of the Form. To be "accurate" or "inaccurate" the memory would have to be something like a truth claim, like you can (mis-)remember that the cat had her dinner. But if what we get through Recollection is more like mastery or competence in the use of a single concept (like "large") it is not clear what misremembering or inaccuracy could even amount to: either you can deploy the concept, or not. But again this would be controversial, as it isn't entirely obvious what is involved in having recollection of a Form.

Thank you for all these podcasts

What a resource is the 'History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps'! Too often, introductory philosophical resources (articles, podcasts, videos) do a poor job, at least for the relatively rushed or for the somewhat uninitiated: either the account is too hard or the account is philosophically and/or textually inadequate. Yet, these podcasts (I've listened to a half a dozen) are sophisticated, yet simple. True, to get the full benefit, one has to take notes (and, thus, pause the playback) but so doing is well worth it. Marvellous! (I add: I do know that there are several books based upon the podcasts.)

If I have one criticism (of this particular podcast) it is this: I don't think that the talk fully explains the diagram that appears on this webpage. Indeed I found that I had to make my own diagrams in order to (begin to!) understand the _Meno_'s argument-from-geometry.

In reply to Thank you for all these podcasts by NJ

Sophisticated yet simple

Thanks! That nice phrase is definitely a good summary of what I am shooting for so glad it is what you have taken away. And yes, podcasts are definitely not the best medium for explaining geometry!

Height and virtue

I have been enjoying your podcasts but take exception to your puzzling yet all-too-common prejudice. At 48 seconds in your piece on Plato’s Meno you praise your listeners for being “slightly above average height and good looking.” (Make that two prejudices.) My husband of 39 years has impeccable morality and discipline that I would stake my life on. He is kind, charitable, learned, and a loving father to our children. In short, a stand-up guy. He is also 5’7”.

I know your comment was tongue in cheek; I even smiled at first. But our society does conflate taller with better, and an honest philosopher ought to take a critical eye to that hurtful and wasteful assumption.

Thanks for the podcasts. I will continue to listen.

In reply to Height and virtue by Barbara

Height

Yes, I see your point. I guess I wrote this joke more than a decade ago so not sure what I was thinking at the time, but if I wanted to defend it in retrospect, I might say that it actually pokes fun at the idea that being taller is somehow better (along with the more obvious joke that all my listeners could possibly be above average height). By the way I am 5'8"!

Add new comment