8. Case Worker: Panini's Grammar

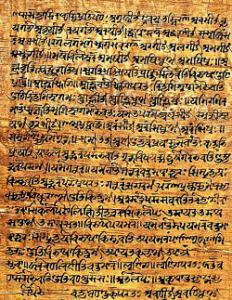

The pioneering Sanskrit grammar of Pāṇini and its implications for philosophy of language.

Themes:

• G. Cardona, “Some Principles of Pāṇini’s Grammar,” Journal of Indian Philosophy 1 (1970), 40-74.

• G. Cardona, “Pāṇini’s Kārakas: Agency, Animation and Identity,” Journal of Indian Philosophy 2 (1974), 231-306.

• P. Kiparsky, Some Theoretical Problems in Pāṇini’s Grammar (Poona: 1982).

• R.N. Sharma, The Aṣṭādhyāyī of Pāṇini, vol.1: Introduction to the Aṣṭādhyāyī as a Grammatical Device (New Delhi: 2002).

• F. Staal, “Ritual, Grammar and the Origins of Science in India,” Journal of Indian Philosophy 10 (1982), 3-35.

• J.F. Staal (ed.), A Reader on the Sanskrit Grammarians (Cambridge: 1972).

Thanks to Malgorzata Wielinska-Soltwedel for her help with this episode!

Origins

..

..

Comments

It is interesting that old

It is interesting that old Indians were able to form a huge literature, including grammar "books", without having a writing system.

afaik, the earliest writing system attested in indian subcontinent is brahmi script, and the earliest examples of that script are dated to around 400bc and no earlier. As the creator of one of the most important literatures of the ancient world, india "discovered" writing surprisingly late. Actually, very late. And when it is introduced, indian literature were already well-developed.

By way of comparison, chinese characters are attested from 1200bc, and mesopotamia/egypt are much older.

Question

First I would like to say that I love your podcasts. You are forming a veritable Bayt al-Hikma for the internet.

Secondly, rather apropos of nothing, what languages can you read? I'm partly interested since what languages a person knows often biases them toward certain cultures and texts that were written in a known language (esp. true because lots of non-European works are untranslated). I noticed, for example, that you focuses far more on Arabic and Persian writers rather than Jewish or Turkish ones (although your podcasts is still a far more comprehensive overview of medieval Jewish thought and Islamic thought than much else on the internet. I'm also just curious because I study linguistics and thus find what languages people know very interesting.

Keep up the good work!

In reply to Question by Ben

Languages

Hi - thanks very much! Glad you like the podcasts. I mostly work with ancient Greek and Arabic on a daily basis, but I also read Latin and have been learning Persian over the past year (but am at a very beginner level). I'm fluent in German, which is handy since I live in Munich; and then I can read but not really speak some other modern European languages which is really necessary to keep up with secondary literature. Still the only language I actually speak other than English is German, much to my regret.

I have often thought of trying to learn Hebrew but given my interest in later Islamic thought decided to attempt Persian instead. And these days I wish I could read Sanskrit...

dhātus not verbal roots

at about 7:13 you assert, as part of your argument that P. puts verbal action at the centre of sentential meaning, the idea that the list of roots, Dhātupāṭha, is a list of verbal roots. That is not so. In the Dhātupāṭha, the dhātus, roots, are arranged according to verbal declensions, and according to their various other features (sārvadhātuka/ārdhadhātuka, seṭ/aniṭ, ātmanepada/ubhayapada/parasmaipada, etc.). But a verb, for Pāṇini is a tiṅanta. The dhātus may evolve into tiṅanta forms, but they may also evolve into subanta, or nominal forms. Dhātus precede the distinction of nominal and verbal words, suptiṅantam padam. They are the roots of all linguistic forms, not just verbal forms.

In reply to dhātus not verbal roots by Dominik Wujastyk

Verbal roots

Thanks for the correction - I see the point. Actually something similar happens in Arabic. As a non grammar expert, I would say that "verbal root" is ambiguous because it could involve a reference to "verbs" as you are taking it, or just "words" (so "verbal root" would mean "root of words generally"; compare "verbal agreement" which means an agreement in words, not an agreement about verbs). Still I take the point that it is misleading. What alternative translation would you suggest? Just "lingustic root"?

Target

Maybe i'm misunderstanding, but shouldn't the ground be the target of the sentence? The leaf falls from tree to the ground seems like donar to target, where as "I dance in the room" seems like room is locus. Otherwise, what is the target?

In reply to Target by Alexander Johnson

Sanskrit grammar

I'm not sure I can explain why Panini does it that way (I think it was his example we used and his analysis of it) without knowing Sanskrit, but perhaps "upon the ground" would be better - like, think of the moment the leaf is touching down, not the moments where it is fluttering down from the tree branch. I guess that "target" is more like an accusative object.

Another excellent episode! I

Another excellent episode! I was surprised to find that Panini's syntactical system is more or less the same system I learned in my Intro to Linguistics course almost a decade ago; it's called thematic analysis, and it's covered in the semantics unit.

Panini's grammar

Hi Peter, I have recently discovered your podcasts and am greatly enjoying them - I have some haphazard knowledge of classical and Indian philosophy and the series does just what it says, fills in the gaps!

Re your reply to a comment on this topic, if you ever get the time, highly recommend learning Sanskrit: as you're a proficient (or much better) reader of Classical Greek it will probably come quite easily as the case system and word order conventions (or lack of) will make you feel right at home, and the differences between Vedic and Classical Sanskrit are reminiscent of the distance between Homeric and Attic Greek. It seems to me (a biased amateur of course) that reading the Upanishads or Sutra/Purana literature in Sanskrit is easier than, for example, Plato in Greek or Heidegger in German (or Heidegger in any language of course), although I do persist with all of the above :-)

Please keep up with the great work with the podcasts, extending our horizons with every episode!

In reply to Panini's grammar by Peter Johnston

Sanskrit

Oh I would love to do that. In the past few years I have learned some Persian and am kind of thinking that, at my age, that might be enough languages. It's not just learning the languages, it's also finding time and chances to keep them all more or less fresh; the podcast has helped with that, for instance it gave me a lot of chances to look at texts in Latin which I don't do enough.

Sanskrit grammar and sentences

For those actually looking for Sanskrit grammar, sentences and intricacies of Panini grammar, can see here yesvedanta.com/sanskrit/tenses

Add new comment