142. Final Chat with Chike Jeffers

How Africana philosophy looked to a young Chike Jeffers, coming into the field in the early 21st century.

Transcript: History of Africana Philosophy 142, Final Chat with Chike Jeffers

Note: this transcription was produced by automatic voice recognition software. It has been corrected by hand, but may still contain errors. We are very grateful to Tim Wittenborg for his production of the automated transcripts and for the efforts of a team of volunteer listeners who corrected the texts.

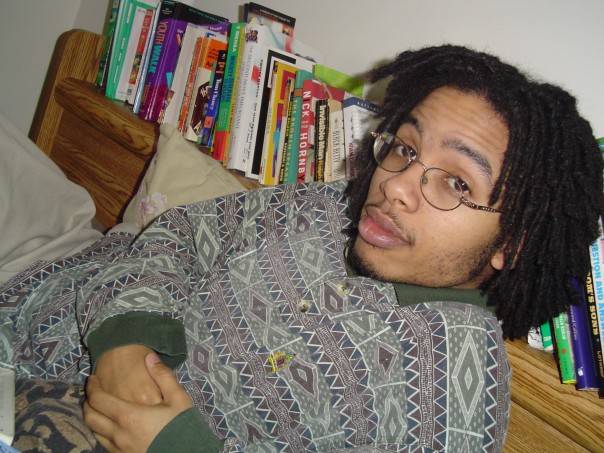

Peter Adamson: Today's installment will be a final chat with co-author Chike Jeffers in which we'll look back at what we've done and also look back at what's happened in the last quarter century of Africana philosophy. Hi Chike.

Nice to talk to you this last time.

Chike Jeffers: Yeah.

Peter Adamson: It's a bittersweet moment.

Chike Jeffers: That's true.

Peter Adamson: I assure you that you're not done.

Chike Jeffers: No, I know that we still have the books to go and who knows I might, you know, end up with the expertise to be interviewed by you on some far in the future topic of contemporary philosophy when you actually get to the 20th century.

Peter Adamson: Absolutely. You will always be welcome, even if you don't have that good excuse.So what we've done in the last, however many episodes - I've lost track myself - is we brought the story up to the end of the 20th century. So let's say that that brings us to the year 2000.

Chike Jeffers: Yeah. 141 episodes in fact.

Peter Adamson: Is that how many? Okay.

Chike Jeffers: Yeah, this is 142 right here. That's where we're, that's where we're cutting it off.

Peter Adamson: That brings us up to the year 2000. And it just so happens that that is the very year that you started out your university studies as an undergraduate. And I think that you were already from the very beginning, you had some interest in Africana philosophy, although I don't know if you would have known to call it that, right? So maybe you can just tell us how, from your point of view, things looked when you started out as a student coming into the field.

Chike Jeffers: Part of what was interesting about my entry into the field is the work done by people in the last few decades of the 20th century that made Africana philosophy enough of a thing that I was led to enter philosophy as a whole because of realizing that there was this thing, Africana philosophy, that existed and that one could study and specialize in as a professional philosopher. So I didn't start my undergraduate degree knowing that I wanted to do philosophy. I had read certain bits of philosophy, including, you know, popular works like, you know, the Simpsons in philosophy, Seinfeld in philosophy, these kinds of popularizing works on my own time. And I started my degree in film, studying film production, but by the end of my second year of undergrad, I realized that I didn't see myself going into film as an industry, and I did at that point know that I was more interested in the academic side of things. That is, you know, what excited me in terms of my film courses were my film studies courses, right? The stuff where we're analyzing things and the stuff where in many ways philosophy was in the background of the stuff that was attracting me when doing film studies courses. So I switched streams. There were three streams in the program: film production, screenwriting, and film studies. And so I switched streams to film studies and I took philosophy as a minor before I had actually even taken a course in it. And the very first philosophy course I took, as I recall, it was titled Existentialism, but it turned out to just be about Nietzsche. And it turned out specifically to be just about Thus Spoke Zarathustra. And I specify this partly...

Peter Adamson: You started out philosophy with Thus Spoke Zarathustra! Wow, talk about diving in at the deep end.

Chike Jeffers: Yeah. And, you know, the reason that I find it worth mentioning is because Thus Spoke Zarathustra and Nietzsche in general have not been particularly important to my writing and publication and things of that nature. And yet, doing that course, I knew that I had made the right choice and that philosophy was what I enjoyed. There was a big confirmation that I was on the right path. But, but I say on the right path, it was confirmation that I really enjoyed philosophy and that I was good at it because of the mark I got, but there were still two important things that needed to happen to me to make me realize that philosophy was something I would want to make a career in. And it's significant that at the time that I would have taken that course, I think I still would have been better able to see why a degree in film studies would make me into what I would think of as a productive community member than philosophy. That is to say, I probably had thoughts of the sort, 'oh, you know, I could be a film critic and we need more black film critics and people who can, you know, organize showings of black films and bring attention to the black contribution to cinema.' Right. It was still at that point easier for me to see how in terms of trying to advance my community, and be, or be part of advancing the community, that film studies somehow still seemed more relevant. Philosophy seems to me to be this thing that was fun, but I didn't really know how in terms of what mattered to me in choosing a vocation, it still wasn't clear to me that philosophy was of use. And this is why two things that happened. First of all, an African philosophy course that I was able to take and a book that I bought George Yancey's African American Philosophers, 17 Conversations.

Peter Adamson: We talked about it in the last episode.

Chike Jeffers: Yeah, precisely. During my third year of undergrad, those two things helped to make me realize that philosophy wasn't just fun. It was also the thing that I could make a career out of and be hopeful that in doing so, I was doing something useful for my community. And it'll be helpful as we start to try and say something about the 21st century and what happens after where we cut our story off in previous episode. It'll be helpful for me to expand a bit on both of those things, the African philosophy course and Yancey's book. So the African philosophy course was taught by a man named Esteve Moreira, who is still a faculty member in the philosophy department at York University. And Esteve Moreira, he's from Spain and he tends to work on Gramsci and Vico. So he's a Spaniard who works on Italians and he does not himself specialize in terms of his research in African or Africana philosophy. However, he taught a course on African philosophy based on him having had enough reading interest in it. A significant thing to note as background for how and why he ended up doing this in the early 2000s when it was still even much rarer than it is today for universities to offer courses in African or Africana philosophy. It's not an accident that Professor Moreira had gotten his PhD from the University of Toronto. And while he was a graduate student in the 1980s, he had been very friendly with Charles Mills, who's someone we discussed in the previous episode, who was also doing his PhD at the University of Toronto, and also Olufemi Taiwo, the elder, who we interviewed for the podcast along with Olufemi Taiwo the younger, and Femi Taiwo the elder, who was as well a graduate student at University of Toronto in the 80s. They were all three graduate students. They were all three men of the left and with various activist connections in that sense as well. It's clear to me that that experience that he had in the 1980s helps to encourage him to offer this course at the time that I was able to take it, you know, in the early 2000s. And so that's one way that I wanted to bring in figures that we've already talked about.

Peter Adamson: I do want to go to the alternate reality where you became a filmmaker and watch your cinematic biography of W.E.B. Du Bois.

Chike Jeffers: You know, that's a lovely thought, in fact.

Peter Adamson: Now you should still do it. More seriously, the other thing I want to say is I think that's a real lesson for everybody - the effect that course had on you. It shows the power of being willing to teach outside your area. But actually, I think a lot of the way that philosophy gets more diverse is people being willing to take the plunge. And even if they're not going to publish in an area, they're still willing to teach it and put students in touch with these topics.

Chike Jeffers: I think that's 100% true. It's a lesson that you are well placed to share with others because of the fact that through the podcast, you're doing that on a very grand scale. So, yes, I do think that this course being taught by Esteve was an example of just that. And one more thing that I'll quickly say about the course is that I remember talking with a fellow student and that fellow student seemed somewhat disappointed by some of the course material. And I got the sense that they had expected to come to this course on African philosophy and hear like, you know, this is the African conception of this, and this is the African conception of that. And the fact that we were plunging into the metaphilosophical debate, the 20th century figures that we discussed particularly toward the end of part one, right? Because that was such an important part of what African philosophy had been in the 20th century, right? I think that he expected to be getting more easily gift wrapped African conceptions of this or that rather than the difficulties and the challenges of this metaphilosophical debate. And it was also the way in which I didn't relate to him at all, and the way in which I was thrilled with what was going on. That was yet another confirmation that, yeah, maybe I'm the kind of person who should be doing this stuff as a career. And coming now to George Yancey's book. And I fondly remember that when I eventually met Yancey and told him about what the book meant to me, he said that I had made his year. That book is extremely important to me. And, you know, it's maybe even hard to say which out of the two mattered more because there's the complimentary lesson that is taught here, right? So if we take Esteve Moreira teaching that course to be saying, hey, people, even if it's not your area, if you make it available to students, that can be very meaningful, right? Well, we would, of course, also agree that people for whom it is their passion and specialty and people for whom it relates to their identity, those are role models and the importance of role models is hard to overstate. And I would say that the importance of role models is hard to overstate in my own case, because that book, African American Philosophers, 17 Conversations. Yeah, I do think that that book more than anything else, and I would actually say yeah, more even than the course, made me think that there are people who have already been doing the work to make philosophy be a place where we can discuss Black issues in a penetrating and thoughtful manner. And thus, it gave me the sense that this is something that I can step into and continue to participate in the work that people have already been doing.

Peter Adamson: And presumably it was also relevant that it's a collection of pieces by a number of different philosophers, right? So if you just picked up a book by one person, you might have thought, oh, here's an interesting person, an interesting author to read, but there you're being presented kind of with a whole field full of people, right? So it shows you that here's a field that you could imagine yourself in, right?

Chike Jeffers: Yes, to be clear, it's not a bunch of pieces by different people. I wouldn't describe it that way, but it's a bunch of different people answering similar questions, right? They're all interviews. All the chapters are interviews, and there are certain basic questions that are repeated in basically every interview. But then of course, also there's unique questions related to the specialization of the thinker in question, right? It begins with Angela Davis and Cornel West, right? So it starts off with these icons that I also would have already known about. And that's a reframing now for me to read this book in which they are being positioned as professional philosophers, even though, of course, the two of them in ways that we've mentioned in the podcast were outside the discipline to varying degrees.

Peter Adamson: We even asked Brother West himself what he's going to say about it. And he gave a very complicated answer, of course.

Chike Jeffers: And it's true. But, you know, in the case of, you know, Cornel West, you have someone who was there, like at the founding moments, like the Tuskegee Conference. And, you know, and he's going to some of these meetings of the New York Society for Black Philosophy. He is in that philosophical forum issue, which is really helping to launch things. So when Cornel West, who is someone I admire very much, when he protests at being squeezed into the box of philosopher, all I can do is take that as telling me interesting things about how he sees philosophy, but not as actually telling me whether I should see him as a philosopher. He truly is one of the pioneers. And he did that work. And he published books in the 1980s that made people think in new and interesting ways about philosophical matters, in my view. He is a philosopher and, you know, he's a philosopher who managed to launch from that particular subject position or occupation, you know, into the role of public intellectual. And he's someone who's embodied that role in a unique and powerful manner. It's still the case that when I think about times I have seen him speak in person, that he's one of the most electrifying speakers, you know, that I've seen. Professional philosophy is in that sense, just one part of him. But to me, a very foundational and important part.

Peter Adamson: And coming out of that book and I guess further reading you did, it would have been pretty clear to you who some of the big hitters were. So you've got West, Davis, Abbie, Outlaw.

Chike Jeffers: Yep. Abbie himself is not one of those interviewed in the book, but I would have come across him during this time, around the time that I was reading that book and realizing that I might want to go into professional philosophy. But what I did start to do actually was write to some of the people in the book.

Peter Adamson: And that is something that we, in fact, very briefly mentioned in our previous episode. That's right.

Chike Jeffers: So, yeah, we had a little reference there to the fact that as I started to realize I wanted to maybe do this as a career, I started to reach out to certain people. And one of those people was Lucius Outlaw, who was, as I say, delighted by my name because he had named his son Chike. And I was another diasporic Chike. That was, you know, the beginning of a wonderful bond between us. And he has meant a lot to me from then on. Another person who is not in the book, but it's in the context of me starting to write to people after having read the book that I contacted him, would be Charles Mills. So Charles is not in the book, but I came across him in some of the things that I was reading. He has a major impact on my development starting at that undergraduate period. I mean, people who know my story may know that he was eventually my dissertation advisor. There was a lot of ways in which he was important to my life from way back before that. And in some ways, it's useful for me to talk about because they, again, help to show how the story where we left it off continues.

One thing that we did in that final episode is we described how, you know, certain figures of Caribbean background were starting to really have an impact in the 1990s. And we highlight Charles, but also Lewis Gordon and Padgett Henry. And Padgett Henry's book, Caliban's Reason, comes out in 2000. And I was reading that book by the time that I had realized I was interested in doing philosophy as a career. It made a big impact on me. It gave me a model for thinking about Africana philosophy. And this is some of the things that we just very briefly hint at towards the end of the last episode. But Padgett, for someone who himself was not trained as a professional philosopher, he's trained as a sociologist, but he had a vision for the building up of philosophy as a profession that was very meaningful and important for me. And one of the things that was created in the wake of that book making the impact that it did was the Caribbean Philosophical Association, which Lewis Gordon and Padgett Henry are involved with from the beginning as founding members and organizers. And as it happened, Charles Mills, I met him on a trip to Chicago while I was still in that third year of my undergraduate degree. By the time I was in my last year, he informed me about the first meeting of the Caribbean Philosophical Association, which was to happen summer of 2004. Or maybe it was even spring, might have been May. It has maybe been like May. And the reason that I think about this is that because of Charles letting me know about that conference, I would warn you to be ready to be slightly jealous of me, because of Charles letting me know about that conference. My very first academic conference took place at a hotel on the beach in Barbados. It was truly the best way to be introduced to what academic conferencing is like, that I can imagine.

Peter Adamson: No wonder you went into philosophy! Very misleading I have to say.

Chike Jeffers: They're not all like that. That's true.

Peter Adamson: I think my first academic conference was in Dayton, Ohio.

Chike Jeffers: Yeah, different from the beach in Barbados, you know, which is no disrespect to Dayton. But yeah, no, it's true. The setting for my first academic conference truly made this seem like a dream come true. And I went having not yet graduated. That was a powerful experience. I was on an author meets critics panel with Paget Henry. So my first experience of academic conferencing, I was an undergrad with two other tenured professors commenting on Paget's book. And it's a moment that means a lot to me, especially in terms of what Paget modeled in that moment. Now, I will say that my critique of the book was very much a constructive critique. I've already said that he very much influenced me. And so it was already a situation in which I was excited about what he was doing with African philosophy and very much on board with it. But I did make this critique about how in the first chapter of the book, he tries to smooth over some of the metaphilosophical debate, some of the tensions in terms of how to retrieve traditional African philosophy. I called the paper Strategies of Organization because I took that phrase from him and I talked about what it meant to deemphasize conflict and contestation in order to make traditional African philosophy this very usable resource for Afro-Caribbean philosophy as a new discourse. And so it's a constructive critique of that type. Let me say that introducing the panel was an elderly man who I think had been a member of the Hegel Society of Barbados. And so I guess he was very excited to be at this conference on Caribbean philosophy, this meeting of the newly formed Caribbean Philosophical Association. But he was, as I mentioned, a very elderly man. And he had mistakenly introduced me as Dr. Dr. Chike Jeffers. And I corrected that at the time, when I began my career.

Peter Adamson: I don't even have a BA!

Chike Jeffers: Exactly. I was on my way to having that BA, but I wasn't there yet. So the doctor was not the appropriate title. But then when Paget was responding to my critique, he made a joke based on the way that things started off. He said, well, you know, let's get this man his PhD right now. And he went on to like concede my entire critique.

Peter Adamson: No way.

Chike Jeffers: Yeah. And the kind of non-combative, truth-seeking critique concession that can really affect you as someone just coming into the field and what you're seeing about the kind of shared pursuit of the truth that you would hope that we as philosophers are always trying to maintain. And that's why I prefaced it by saying it was a very constructive critique. But nevertheless, that meant a lot to me. You know, the last thing I'll say before I let you ask another question again, I've enjoyed going on this trip down memory lane, but I have to have to be especially thankful to Charles again, because I had a girlfriend who had come with me to Barbados and she had a camcorder and she recorded my talk. And in the wake of the talk, you know, people are saying very nice things to me, this undergrad who seemed to do very well on this panel with these, you know, senior figures. And I was getting a lot of congratulating. And then when I spoke with Charles, he said something like, oh, it's good. You know, we just need to work on your presentation style. And, you know, I didn't think much of that in the moment. And I went back to, you know, having conversations with people who seemed extremely impressed with me, you know, but when I did eventually watch the recording of the talk and I saw myself barreling through in a monotone, you know, and just the kind of, you know, what you'd expect really for someone who's never presented before. Right. This was my first time doing this. So it's not as if how bad a speaker I was was surprising, let's say. But it's one of those moments that makes me fondly remember Charles, who we should say, because it's not something we said in the last episode. Charles passed away, unfortunately, a few years ago now, I think 2021. So one of my very fond memories of Charles was the way that he had my professionalization in mind in that moment.

Peter Adamson: He knew what he was talking about because I went and saw him give a talk in Berlin. And he was absolutely one of the most riveting speakers I've ever seen at a conference.

Chike Jeffers: Precisely. I got advice from the best. Precisely. Yeah. It gave me this desire to live up to what he was seeing in me, right. And to not be satisfied with it being impressive how young I was, but rather to see what's the next step of improvement. And there's things that I would like to say about my dissertation that would be, I think, also relevant to the story, but I'm not sure if we want to go straight to that or if you have another question.

Peter Adamson: I did have a bit of a more general question. Yeah. So it's pretty clear that your sense of who the players in the field were, not just the people we talked about amongst the professional philosophers, but also, you know, people like Watunji and Oruko and Mbiti, you would have gotten to know about them through that class, actually. But I'm wondering what your sense was of the main philosophical issues and debates. So obviously the whole metaphilosophical thing like philosophy and oral traditions was another thing that was being debated a lot at the time. The thing that we mentioned in the last episode about biological versus socially constructed theories of race, was that kind of where the field was coalescing or was that just one of many things that was being discussed at the time?

Chike Jeffers: It is one of many in an important sense, but it was a particularly important thing. I'll say that. So in my father's house, Africa and the Philosophy of Culture, that's a book by Appiah that we mentioned in the previous episode. I would have read that around this time as well, before I even entered graduate school, that book's from 1992. And Appiah is an interesting figure for me, just because I, I think, reacted very negatively to my first reading of Appiah. I don't think I ever doubted that he was an interesting thinker, but I think I was pained by how wrong I felt he was in terms of the ways that he was seeking to push the idea that there are no such things as races. And he was also at that time pushing a conception of racism, according to which much of the ways that people think of Pan-Africanism would be racist. And so I reacted very strongly against that.

Peter Adamson: So why would Pan-Africanisms be racist on Appiah's view or why would it be in danger?

Chike Jeffers: Yeah. He ends up making this distinction between external racism and internal racism around this time where external racism, and I am going to be saying all of this from memory, so hopefully I'm not getting any details wrong, but external racists have preference for members of their race on the basis of external criteria. That is, for example, criteria of how this or that race is allegedly better than another. And so sort of what you would traditionally think of racism is going to involve that external component, right? The idea of ranking races on a hierarchy of value. As I recall, the contrast, internal racism involves preference for members of your own group where that's not based on the idea that your group is superior for this or that reason.

Peter Adamson: It's not we're better than that. It's just we are us.

Chike Jeffers: Exactly. So something like that. And so he argued that both are morally troubling, you know, even though in different ways, and even if we might say it in certain ways that external racism is more clearly troubling and so on. And yeah, so the way that he was thinking of race and racial identity at that time, a traditional investment in Pan-Africanism, particularly in the racial mode of thinking of it as a commitment to the Black world or something of that nature. He at that time had been giving certain arguments for this as investing in a false idea of race itself and also having a morally substandard way of thinking about who you should be cooperating with and in allegiance with and so on and so on. The fact that I came to all of this with very Pan-Africanist inclinations, that's a story that just goes back to childhood in terms of influences from my parents and other aspects of the way I was raised. Then, you know, I think that that naturally made Appiah someone that I had problems with. If you look at reviews from the time and if you look even at, you know, Molefi Asante wrote about Appiah's book. And if you look at the way that a number of figures at the time are reacting to Appiah's book, then, you know, you'll see some of the reactions that would be similar to the one I had in terms of his attempts to push us away from notions of race. And even as we mentioned that he attempted to uphold his father's Pan-Africanism, it was already something that he was working out in a way that was meant to push away from what he thought were traditional ways of thinking about racial solidarity and that he thought were shot through with various theoretical and practical problems.

And that is a fine way to also start talking about what I ended up doing the dissertation on and how that helps us say a bit about what was happening in Africana philosophy. But I do want to, before I go further, sort of come back to the origin of your question, right, where you were wondering if this race stuff was kind of like just one among many things or sort of like becoming the central deal or whatever. Yeah, I think it's relevant that only at some point in graduate school, when I was already pursuing a PhD, when I think I maybe already had in mind some of what I wanted to do for the dissertation, did I really start to embrace philosopher of race as like an identity, if I could put it that way, to something like the same degree that I took Africana philosophy to be what I was here for. Right. And so I'm saying that, you know, for a few reasons to once again sort of point out how it's unique that I came along at a time when so much of the work had been done that I could take Africana philosophy as my reason for being in the field. But I also bring it up to say that it is remarkable that the Appiah Outlaw debate that we discussed in our previous episode, you know, was such an important part of how philosophy of race came to be a thing in the way that it is among professional philosophers today. Right. It was in that sense, this interesting outgrowth of Africana philosophy, right. Both of them are looking back to Du Bois and other people like Tommy Lott and Bernard Boxel that we mentioned and also someone we didn't mention, but who it will be important for me to mention now, Robert Gooding Williams. These people are responding to Appiah and to Outlaw. In the case of Bob Gooding Williams, he wrote on both Appiah and Outlaw shortly after this debate is taking place. On one level, this is a debate about how best to understand Du Bois. And in that sense, it is this important part of the tradition that we can call Africana philosophy. But at the same time, because race, I mean, the interesting thing about, you know, talking about philosophy of race in the Western tradition is that on the one hand, we could say that it's very old. We want to go back to people like Immanuel Kant and other European figures of the 17th and 18th centuries who were basically foundational in terms of the idea of race coming into being, so to speak. But then for perhaps certain obvious reasons, race doesn't become this central topic that professional philosophers are talking about. And the whiteness of the discipline is part of that, right? It's part of it not being treated as a particular topic to lock in on and debate. And so by the time that Appiah and Outlaw and others are tackling this question of how to understand Du Bois in the 1980s as professional philosophers, then it is this opening for professional philosophers to start taking race seriously in a way that they hadn't done before.

I think it's actually important that philosophy of race is not the same as or a department of necessarily Africana philosophy. You know, I think that it's important that it's a field where all of humanity is the automatic focal point, because the question is, are all of us as humans divided into these groups that are called races? What does that mean? And so on and so on. I think that it's important that it shouldn't be understood as just naturally a part of Africana philosophy. But I just think that it's also historically interesting that the way that it came into prominence is by debates among black philosophers in what we could call a tradition of Africana philosophy.

Peter Adamson: Yeah, that actually is a misconception that our series could have helped dispel for some listeners that they would think, OK, oh, it's Africana philosophy about, well, we even define it as philosophy bound up with the concerns of people from Africa and the diaspora. And so they would think, oh, OK, I see this is a kind of philosophy that's sort of defined in terms of race. But actually, although there have been issues in the philosophy of race coming up constantly, there's been all kinds of other stuff. There's been, you know, feminism, political philosophy, and metaphilosophy, as you said, like, you know, does the question of whether oral tradition can count as philosophy, is that about race? No. So the two things intersect very much. But they're really not the same thing at all.

Chike Jeffers: That's correct. Right. And you can say that it's been this important part of our story. But of course, it becomes an especially important part of our story after a certain point, because at a certain point when you're talking about the modern world and the creation of the diaspora and so on. Yes, it's true that from that point, you're going to have it as this necessarily recurring concern. Right. But it is not, of course, a concern that is central to, let's say, what people are doing in ancient Egypt and what people are doing, you know, in sort of the oral traditions that we're looking at. But I will add to that that as Lucius Outlaw himself, I think, is able to express well in some of his writings on African philosophy. It remains the case that when this started to be a debate among professional philosophers because Africans were going into the field, then it was even when about stuff like what to make of oral traditions, it was even then necessarily taking place within the context of Africans having been colonized, Africans having had European institutions of education as their ways of advancing in a colonial and post-colonial context and the assumption that philosophy is a European thing. Therefore, it's the starting point that they are then faced with and that they have to react against. And so even in that sense, African philosophy is, you might say from the start, also about the question of race.

Peter Adamson: OK, well, let's come back to the question that we kind of deferred because the listeners probably still waiting to know, OK, what was Chike's PhD? Tell us what your PhD was about and how it fits into the story.

Chike Jeffers: Yeah, that's right. Part of what shaped the PhD were the people who had available to me as a graduate student at Northwestern at that time. Charles Mills does come back into the story, but he actually comes back into the story relatively late into my work on the PhD. That is to say, when I chose Northwestern as the place where I would do my PhD, he and I were happy that I was coming to Chicago because he was at UIC. So we were glad that I was going to be in the same city. So the two people who I'm working with when I have first arrived is Suleiman Bashirjanya, who we had on the podcast talking about philosophy in Islamic sub-Saharan Africa, and Robert Gooding-Williams, who I've mentioned, he had gotten his PhD, I want to say at Yale, in the early 80s. He, in fact, early on wrote on Thus Spoke Zarathustra. So that's yet another time that that book is coming up in our podcast.

Peter Adamson: That famous introduction to Africana thought!

Chike Jeffers: That famous introduction to Africana thought! But he also, still in the 1980s, he begins to show serious interests in Du Bois. Suleiman Bashirjanya or Bashir as I'll call him, right? So Bashir works on lots of things, including the topic that we interviewed him on, Islamic philosophy in sub-Saharan Africa. He's from Senegal. And so he had even met Leopold Senghor, and he arrived at the point of wanting to write a book on Senghor. And so Bashir was working on a book that was actually published called Leopold Sedar Senghor, La Africaine comme Philosophie. So Leopold Sedar Senghor, African Art as Philosophy. Bob was working on a book, which at that time, the working title is called something like Contributions to the Critique of White Supremacy, which I still think of as an awesome title. But eventually it was renamed In the Shadow of Du Bois, Afro-modern political thought in America. Some listeners may already know that I, in fact, ended up translating Bashir's book. So African Art as Philosophy, Senghor, Bergson, and... I'm forgetting the subtitle now. Anyway, Bashir's book on Senghor was translated by me. And it's also something that I talk about that with happiness now. For a long time, I was really annoyed by the fact that a copy editor had made changes to my translation before it went into print. And if anyone told me they were reading it, I would ask them their email address so I can send them my list of errata. But it's out in a new edition with a very cool cover. So yeah, look up Suleyman Bashir Janya, African Art as Philosophy. The corrections have been made. And so I'm now proud of this work. But I say all this to say with Bashir working on Senghor and Bob working on Du Bois, it became natural for me to focus on Du Bois and Senghor in my dissertation. And so my dissertation was called The Black Gift, Cultural Nationalism and Cosmopolitanism in Africana Philosophy. And the first part of it was broadly historical with a chapter on Du Bois, a chapter on Senghor and preceding that a chapter on the German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder, who presages some of what I was talking about in Africana Philosophy and the other important figure of that first chapter who I learned for the first time back then, I was fascinated by is Edward Blyden. It's amazing how as we've talked about it in conversations that we've had with the podcast before, I became even more impressed by the importance of Blyden as we did our work on this podcast, but I knew he was important then. And so I had a dissertation, the first half of which was importantly this history of Africana philosophy, looking at Blyden, Du Bois and Senghor. And then the second half of the dissertation was me trying to intervene in contemporary debates. And I won't say anything about the fourth chapter, which was more interested in figures in contemporary Western political philosophy. But my main target in the fifth chapter was Tommy Shelby. And my main target in the sixth chapter was Kwame Anthony Appiah.

So Appiah, we've mentioned already, one of the things he did as the 2000s went on was he started to publish a lot on the topic of cosmopolitanism. And a lot of people now know him for that topic. Right. And there's a way in which this theme of cosmopolitanism further reinforced in certain ways the ways that his work had been about not dividing ourselves by race in past work of his. Tommy Shelby, who is at Harvard, I was able to read some of the articles that were leading up to his 2005 book, We Who Are Dark, the Philosophical Foundations of Black Solidarity. I was able to read some of that stuff, you know, and then when the book came out itself, it made a big splash. I think it's absolutely one of the most important books in Africana philosophy. In the 21st century, helps to also cement his place as philosopher and as a philosopher at Harvard. But this book was very important because in a sense, what Shelby was doing was looking back at the tradition. He talks about Martin Delaney. He talks about Du Bois. He looks at certain figures, you know, from the 1960s, but he looks at Black Power by Stokely Carmichael and Charles Houston. He revisits the tradition and he's in a sense, I think, asking, what do we make of this idea of Black solidarity, Black nationalism in the wake of critiques like those that Appiah was offering? And he argues in the book that we should retain Black solidarity and Black nationalism as an important part of the struggle against anti-Black oppression. But he argued that in order to do that in a way that best reflects what we can say about race and ethics, the ethics of racial identity, you could say that he responds to Appiah's critique of these kinds of investment in race by saying, well, we need to jettison Black cultural nationalism and we need to see Black nationalism as something that there's a convergence on certain political concerns that makes Black solidarity a meaningful part of trying to end anti-Black oppression. But backs off of the idea that Black people just naturally form this group that should see itself as in solidarity and as unified and so on. He steps away from the idea that Black solidarity is something eternal, right? It's something that he questions in the book, right? And says that it's for this political basis of struggle. And as for what happens when you defeat racism, I mean, maybe Black people continue to associate with each other or maybe they don't, you know, who knows? And so what I was doing in my fifth chapter where I was arguing for a non-essentialist Black cultural nationalism is what I aimed to argue for in that chapter. I was responding to that very important work of Tommy Shelby. And I was arguing in response to him that just as he looks back to the tradition of Black nationalism and tries to say what he thinks is important in it, I, through my looking at Blyton and Du Bois and Senghor, am looking back at what's important about Black cultural nationalism and saying that we can save it. We just have to see how it's possible to do like a non-essentialist version of it. And then the final chapter, I tried to argue for the importance of a very intentionally anti-Europe-centric form of cosmopolitanism building on Appiah. So that's just some of the ways in which I was reacting to the currents of the time.

Peter Adamson: I can't help saying, I mean, obviously I have a kind of biased perspective on this because I see you primarily as my co-author on the podcast. I can't help thinking from that whole story, the conclusion that you were unwittingly designing yourself to be the perfect person to do a podcast on the history of Africana philosophy, right? Because you had covered oral traditions and the whole debate about that. You had covered Negritude, you'd covered Du Bois, you covered Blyton. So you even knew something about like the transition from 19th to 20th century. Knew all about the people in the latter part of the 20th century. For you, you were, I guess, just went through the podcast. You were more like filling in gaps, so to speak, around the things that you knew. But this is something I've always been kind of amazed by. Like, how does Chike know all this? Because, I mean, something else I could tell listeners, because this is all something that happens behind the curtain. So when we first started, Chike sent me a list of possible topics. And it's not exactly what we did, but it's close. I mean, we said, we certainly added episodes asw e went along.

Chike Jeffers: I would say the main difference, I would say that it's part three, that that part three balloons, you know, part three in the original plan was not that different in size from parts one and two and part three, part three on the 20th century. That balloons.

Peter Adamson: I think we always were planning to do George Clinton and P-Funk.

Chike Jeffers: Yes, that's true. We knew that that was a connection that we had, you know, going back awhile. I mean, so, you know, it's funny to just build on your point. It delighted me to be able to write as we were working on the final scripted episode, that the very month of my birth is the month when the phrase Africana philosophy was first officially used at that conference at Haverford, organized by Lucius Outlaw. And if there was our counterparts in 2124, you know, working on the story of the 21st century, then it might be nice for them to say how I got my job at Dalhousie in 2010, started like I moved to Halifax by August of that year. I flew back to Chicago to defend, I want to say maybe October of 2010. And within a couple months of that, I started listening to a new podcast called the history of philosophy without any gaps. And little did I know that it would become extremely important to my life.

Peter Adamson: Well, you were literally put on earth to do this then.

Chike Jeffers: I love that someone I know posted a video. It was the jazz teacher talking about Sun Ra and the students were asking why he's so weird, why does he dress that way? And the professor was saying, well, you know, doesn't he have the right, you know? So it stuck with me as I thought about just the weird person and individual that he was, what it means to disrupt things. And Sun Ra certainly disrupted things in interesting ways. And I don't say that to say that I see myself necessarily primarily as someone who disrupts things because I also emphasize for myself the constructive role, the way that, you know, because people like Lucius Outlaw had done what they did, I'm able to help, if you want to put it that way, continue disrupting philosophy with the work that I do on Africana philosophy.

Peter Adamson: All right. Well, that's an amazing note to end on, I think. I can now announce for those who don't know yet that what we're moving on to do from here is classical Chinese philosophy with a new co-author, who's Karyn Lai from Sydney in Australia. So that's coming actually in two weeks. We're going to keep churning these things out. For now, it remains only to thank you, Chike Jeffers, so much for doing this series with me. It's been an amazing trip.

Chike Jeffers: It has been an amazing trip. And I enjoy the fact that I get to be a listener again, just a listener, as you embark on this wonderful journey of reading and talking and thinking about classical Chinese philosophy. It's a hugely exciting area. And I look forward to learning a lot from you and Karyn Lai.

Peter Adamson: Yeah, we'll certainly learn a lot too. Okay. Thanks again to Chike and thanks so much to the audience for following us through these many episodes on Africana philosophy. Please join me next time for the History of Philosophy in China. And with that, that's the end of the History of Africana Philosophy.

Comments

Add new comment