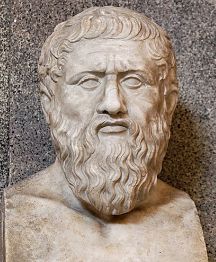

18 - In Dialogue: the Life and Works of Plato

Posted on

In this episode, Peter Adamson of King’s College London discusses the life story and writings of Plato, focusing on the question of why he wrote dialogues.

Themes:

Further Reading

• J.M.Cooper and D.S. Hutchinson (eds), Plato, Complete Works (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1997).

• G. Fine (ed.), Plato 1: Metaphysics and Epistemology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999)

• G. Fine (ed.), Plato 2: Ethics, Politics, Religion, and the Soul (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

• R. Kraut (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Plato (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

• A.S. Mason, Plato (Durham: Acumen, 2010).

Comments

Order of Dialogues

Hi Peter,

Do the works of Plato have a known chronology; what order should one read them in? And the big question, what do philosophers and historians say regarding the Socratic problem? How do we know anything we attribute to Socrates is genuinely true?

Thanks for the amazing work by the way!

Leo

In reply to Order of Dialogues by Leo

Plato

Well, the Neoplatonists had a very firm idea of the right reading order of the dialogues but I don't think anyone would presume to prescribe one today. Generally speaking, there is the idea that the dialogues fall into early, middle and late, as I explain in the first Plato episode (the one on this page). I tend to think that any dialogue can be read on its own though, so it may be more a matter of what topic interests you most.

As for the historical Socrates question, I think I probably said in the podcasts that I'm fairly dubious about the prospects of extracting an accurate picture of Socrates from Plato. Xenophon might be a more accurate source but he also has his own axes to grind. Perhaps one could say that the points on which Aristophanes, Xenophon and Plato agree are secure, but the overlap is not big!

can you help with this reference?

Hi Peter,

a friend is trying to track down the source of the quotation "Man: a being in search of meaning" said to be from Plato. Can you point him in the right direction?

Thanks for the whole series- I am still with you from beginning to Islam and it's the light of my life.

In reply to can you help with this reference? by Joan Kerr

Re: Man in search of meaning quote

Hello Joan and Peter,

It may be a little late to settle the matter, but for anyone who cares: the quote is actually by Abraham Joshua Heschel, who is responding to Ernst Cassirer, himself summarizing Plato's work. (I didn't track these down myself entirely. Someone else had had the same question as you, and a friendly soul took the trouble to answer it; I'm just relaying it after checking the sources.)

Cassirer, Ernst. An Essay on Man, p. 20. https://archive.org/details/ErnstCassirerAnEssayOnMan/page/n18/mode/1up?q=Plato

Herschel, Abraham Joshua. The Insecurity of Freedom, p. 163. https://archive.org/details/insecurityoffree0000hesc/page/160/mode/1up?q=%22In+search+of+meaning

Friendly soul's answer: https://latin.stackexchange.com/questions/16177/did-plato-describe-man-as-a-being-in-search-of-meaning

Authentic Dialogues

Just curious, which of the disputed dialogues (Hippias Major, Fist Alciblades, Clitophon, Spistles, Menexenus) do you think are authentic? Of the ones that aren't, do any of the ones written by PseudoPlato worth reading?

In reply to Authentic Dialogues by Alexander Johnson

Authentic dialogues

I don't have settled views on all of those but wrote a paper on the Menexenus recently and am convinced it is genuine; I also tend to think First Alcibiades is authentic. Apart from that, not sure and particularly not sure about all the Epistles. But these are all worth reading, I would say, as being at the very least evidence for how Plato was being constructed as an author already in antquity.

Book reference

Which copy of the complete works of Plato is the one you mention or is there a version you would recommend? Thank you!

In reply to Book reference by Grisy

Complete works

I'd go for the one published by Hackett, edited by John Cooper.

Re: Plato's Apology

This is my theory regarding the Apology:

Socrates is not the one on trial. It is the affidavit.

Why do I think this? Socrates says he is defending himself, but his arguments prove true every charge.

He has "corrupted" the youth. He has formed heretical ideas about deity. He has challenged the institutions.

But we need Socrates. He challenges us to come after him every way we can. That means that to emulate Socrates is not to imbibe him, it is to question him with a searching critique.

Every shooting range needs targets. It is how we refine our ideas.

The Apology argues that it is wrong to restrict philosophy. And philosophy is inherently a rebel against the State.

In reply to Re: Plato's Apology by Luke

Apology

Yes I definitely agree that the Apology is passing judgment on the trial, not the trial passing judgment on Socrates! In fact Socrates seems to be doing that himself in the dialogue (worth comparing to the version in Xenophon by the way). I am not quite with you on the last sentence though: obviously quite a few philosophers have been rebels but there are also conservative, even reactionary philosophers (Burke, for instance) and in fact Plato himself has more than a few conservative elements in his thought. In fact one of the intriguing things about Plato is how he can seem "reactionary" and "revolutionary" in the same text, notably in the Republic.

Plato's Progress

Hi Peter,

In Plato's Progress (1966), Gilbert Ryle argued the Plato's dialogues were meant to be performed on stage. (I remember Ryle suggesting that the reason why Socrates has smaller parts in the late dialogues is that he was played by Plato, who by then was getting too old to play a big part.) I've never seen this hypothesis being discussed anywhere else. Is there a good reason why it is ignored?

As it's the first time I comment here, I take advantage of the opportunity to thank you for your wonderful podcast!

David

In reply to Plato's Progress by David

Performing Plato

I think probably the lack of discussion has to do with the fact that there is no evidence one way or another so we would be in the realm of speculation. Though also, some dialogues seem impossible to "perform": think of the length of the Republic or Laws, or what it would be like to sit through the Parmenides as a "play". Obviously dialogues, or parts of them, could well have been read out even just in the Academy, but we just don't know.

And thanks, glad you like the podcast!

In reply to Performing Plato by Peter Adamson

Another example might be…

Another example might be Charmides. I mean, why make a play about two people talking to each other about something that happened rather than, you know, about what actually happened? Charmides would make much more sense as a play like that, but makes absolutely no sense with how it is as just two people speaking to each other.

In reply to Another example might be… by Andrew

Framing

Good point! Actually that is common in Plato, for instance the Phaedo is inside a dramatic "frame" and the whole Republic is Socrates telling about a conversation he had (so it would in fact be a monologue, if performed).

In reply to Framing by Peter Adamson

Re: "Another example" and "Framing"

Thank you, Peter and Andrew, for your replies. I think it's true that Ryle's hypothesis is very speculative. Still I find it surprising that the idea that some of Plato's dialogues "compete at the Olympic Games or one of the Athenian Games" is almost never mentioned, even in passing, in books (or podcasts ^^) about Plato.

I'm not sure that the framing (in the Charmides, Phaedo, etc.) is much of an issue for Ryle's hypothesis. Maybe the point of the framing was precisely to get a text that can be performed by only one or two actor(s). Assuming that the texts were not meant to be performed, I don't know what the point of the framing could be. (But there are a lot of things I don't know, especially when it comes to literature...)

In reply to Re: "Another example" and "Framing" by David

There are other potential…

There are other potential problems I can think of.

One is that the dialogues contain a lot of material and ideas to think and mull over, not something you can do while your attention is focused on watching a play.

Plus, Plato I believe (although I can't quite find a good quote for this at the moment, maybe Peter can help) thought that Philosophy is done best through dialectic, or a conversation between two people with the aim at getting at the truth, which is modelled by dialogues (that is one reason why I think he wrote in the dialogue format, but the SEP has a section on the question "why dialogues" if you want to have more reasons on why. See the link below). And, according to Plato in the Phaedrus, he warns against relying solely on books for philosophical development but that the best use for them is as aids to conversations about the same ideas. With this conception of the proper method of philosophy in mind, it makes no sense (to me anyway) to make philosophical plays, where people can't interact with the ideas being presented, nor argue with either fellow audience members or actors about the ideas at play. With books, you can discuss with other people, or at least take time to wrestle with them yourself. You can't do either with a play when what is going on comes and goes in basically an instant and you have to pay attention to follow along.

Finally, why would Plato want to make plays of just one or two people, like you suggest? All other plays in Ancient Greece at the time as far as I know were made with the idea in mind of having lots of characters, props, drama, action etc. Plato's plays by contrast would be very austere on all of that. Why? What would give him the incentive to write a play like that? Was he worried that there wouldn't be many people to play them or something?

Here is the link I was talking about: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/plato/#WhyDia

Add new comment