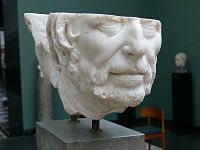

65 - Anger Management: Seneca

Peter starts to explore the Roman Stoics, beginning with Seneca and the Stoic attitude towards the emotions.

Themes:

• S. Bartsch and D. Wray, Seneca and the Self (Cambridge: 2009).

• M.L. Colish and J. Wildberger (eds), Seneca Philosophus (Berlin: 2014).

• J. M. Cooper and J.F. Procopé (ed. and trans.), Seneca: Moral and Political Essays (Cambridge: 1995).

• C. Gill, The Structured Self in Hellenistic and Roman Thought (Oxford: 2006).

• M. Graver, Stoicism and Emotion (Chicago: 2007).

• M. Griffin, Seneca: a Philosopher in Politics (Oxford: 1992).

• B. Inwood, Ethics and Human Action in Early Stoicism (Oxford: 1985).

• B. Inwood, Reading Seneca: Stoic Philosophy at Rome (Oxford: 2005)

• B. Inwood (trans.), Seneca. Selected Philosophical Letters (Oxford: 2007).

Stanford Encyclopedia: Seneca http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/seneca/

Comments

This was a fantastic episode,

This was a fantastic episode, thanks you Peter!

Fantastic!

Thank you! Wonderful broadcast!

Great episode! Seneca is one

Great episode! Seneca is one of my favourite philosophers, since his teachings are so eminently practical. His works are always not far from by bedside table. The Letters to Lucilius are delightfully real.

Of all readings mentioned above, which one would you recommend the most?

Keep up the good work!

Cristina

In reply to Great episode! Seneca is one by Cristina

Seneca readings

Hi Cristina,

Glad you enjoyed the episode! That's a difficult question, because the readings I recommend here are very different. Griffin is the best work on his life, as far as I know; the selected letters perhaps a good place to begin reading his actual philosophical works. But for a philosophical discussion at a high level I'd go with one of the Inwood volumes. To me he's the leading scholar on Seneca's philosophical thought. (Gill is also excellent but not mostly about Seneca, I put that on because it gives the context regarding theory of the emotions.)

Hope that helps,

Peter

In reply to Seneca readings by Peter Adamson

Seneca and Epicureans

Dear Peter:

Thank you very much for the recommendations. I will check Inwood's books.

Reading Seneca's letters to Lucilius, I was struck by the amount of Epicureanism that he deploys, especially in the first half of the work. In fact, not only he acknowledges that many of Epicurus' ideas were right, he also seems to incorporate them to his own philosophical core.

I know that the addressee, Lucilius, was in fact an Epicurean, and I suspect it could be a way for Seneca not to overthrow his friend's philosophical stance in a whole. However, I was wondering up to what point Seneca is a real 100% Stoic, rather than a mixture of, let's say, 70% Stoicism, 30% Epicureanism (of course, percentages may vary).

In fact, that mixture of traditions is one of the reasons why I see Roman philosophy as an interesting development. It was a long way for Romans since the second century BC, when a governor in Athens decided to have the leading men of all philosophical schools plead before him in order to later decide which one was right!

Cristina

sense of humour

love your sense of humour

An excess of anger.

Seneca compares outrage to running off a cliff and he's right. Biologically, anger is a function of the amydala, an almond-shaped structure in the midbrain. It controls the "fight or flight" response. Once it gets activated it's hard to stop it. When you really "lose" your temper, psychologists call it beeing hijacked by your amygdala.

Seneca: Stoic or Cynic

My understanding from the podcast was that Seneca was a Cynic, but the show notes above call him s stoic?

In reply to Seneca: Stoic or Cynic by Steven Cartledge

Stoic/Cynic

Not sure how you got that out of the podcast, but Seneca was definitely a Stoic, one of the leading figures in the later, Roman part of that tradition along with Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius.

Buster

Best appeal to Buster Keaton in the history of philosophy, if not history full-stop.

Seneca, Stoicism, Tacitus and the Misapplication of Wisdom

Many years ago I listened to this episode but only recently have I read the Histories and Annals of Tacitus. Though very interested in philosophers, I am more interested in historians so, therefore, while spending hours plowing through Tacitus I still haven't read Seneca. Nonetheless, from my reading of Tacitus, Seneca did not fare well in his application of philosophy. While he did die because he was ordered to commit suicide and by Tacitus' account did not stop philosophizing up to the point when he took his life at Nero's order it seemed still a lot of "waxing eloquent." To die by forced suicide was so common and by all ends of the moral spectrum that I would not count it in his moral favor to have done so. I've moved on beyond Nero's reign and while working my way through the horrid "year of the four emperors" the following anecdote of a Stoic philosopher could use some commentary regarding a study in futile attempts to apply philosophical wisdom to an impossible situation. In an attempt to stop the endless bloodletting between armies loyal to Vitellius and those loyal to Vespasian, the Senate of Rome send an envoy to both armies to appeal to the generals and soldiers to negotiate so the Empire could finally have a respite from civil war. The envoy was not only unsuccessful but came close to finding its mortal end because of a Stoic philosopher named Musonius Rufus that came along with them. Tacitus relates:

"One Musonius Rufus, a man of equestrian rank, strongly attached to the pursuit of philosophy and to the tenets of the Stoics, had joined the envoys. He mingled with the troops, and, enlarging on the blessings of peace and perils of war, began to admonish the armed crowd. Many thought it ridiculous; more thought it tiresome; some were ready to throw him down and trample him underfoot, had he not yielded to the warnings of the more orderly and the threats of others, and ceased to display his ill-timed wisdom." -Tacitus History Book III Chapter 81

In reply to Seneca, Stoicism, Tacitus and the Misapplication of Wisdom by Philip Riske

Pragmatism

Sometimes, you just have to pick a side.

Add new comment