55 - The Constant Gardener: Epicurus and his Principles

Peter begins to examine the philosophy of Epicurus, focusing on his empiricist theory of knowledge and his atomic physics.

Themes:

• C. Bailey, Epicurus: the Extant Remains (Oxford: 1926).

• S. Everson, “Epicurus on the Truth of the Senses,” in S. Everson (ed.), Companions to Ancient Thought 3: Epistemology (Cambridge: 1990), 161-83.

• D. Furley, “Knowledge of Atoms and Void in Epicureanism,” in J.P. Anton and G.L. Kustas (eds), Essays in Ancient Greek Philosophy (Albany: 1971), 607-19.

• D. Glidden, “Epicurean Prolepsis,” Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 3 (1985), 175-217.

• J.M. Rist, Epicurus: an Introduction (Cambridge: 1972).

• G. Vlastos, “Minimal Parts in Epicurean Atomism,” Isis 56 (1965), 121-47.

• J. Warren (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Epicureanism (Cambridge: 2009).

Comments

Epicurious' Birthday

So, what is his birthday?

Love your podcast.

In reply to Epicurious' Birthday by Sam Glenn

Happy birthday Epicurus

Hi Sam,

Funny you ask, in my original script I had him being born in January and it said "you should clear a space on your calendar each January..." in the first paragraph. But then when I was revising before recording it I couldn't remember where I had this from, and couldn't find it in any of the books I had here... so I took it out. But I think it's probably January, I was just playing on the safe side.

Thanks,

Peter

Epicurus birthday

I saw a book on Google Books - "Paradosis and Survival: three chapters in the history of Epicurean philosophy" by Diskin Clay. This says the date was on the tenth day of the month of Gamelion - whenever that was! This was apparently quoted from Epicurus' will.

Gamelion seems to run from about mid January to mid February so January sounds reasonable. (About the 25th?)

In reply to Epicurus birthday by CarolA

Gamelion

Thanks Carol -- it's coming back to me now, there was some mention of the month Gamelion in what I read. So I guess I should have been brave and stuck to my original text! I suspect I found the date in the Cambridge Companion to Epicureanism edited by James Warren (which is really good by the way, I found it helpful).

Peter

In reply to Gamelion by Peter Adamson

Thanks for the book tip - and

Thanks for the book tip - and it is in our Uni library. Something to read over the summer break.

Book recommendations

I really like the sound of Epicurus - friends, conversation and atomism. I would like to get a book on this 'school'. (I have noticed the 'further reading' list on epsiode 55)

FolIowing your recommendation I purchased James Warren's 'Presocratics' and really liked it. And the cover was really nice!

I was wondering whether you had read any of the other books in the 'Ancient Philosophies' series and would care to recommend any?

http://www.ucpress.edu/series.php?ser=aph

By the way, it was great to hear you, Angie Hobbs and James Warren discussing Heraclitus on In Our Time today. :-)

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b017x3p4

Correction

Hobbes hence no Epicurean, it would seem

Presently studying Hobbes, it occurs to me that it hence seems dead wrong to count his theoretical philosophy as Epicurean, as is frequently done. -- His materialism certainly countenances no such thing as the atoms randomly moving in a void, swerving from their paths without cause. This whole idea that the world is not deterministic is this way is very opposed to Hobbes's thought, not to mention the further idea that this indeterminism might somehow explain the possibility of freewill. -- I take it, that this notorious latter idea is not part of Epicureanism either, right?

In reply to Hobbes hence no Epicurean, it would seem by Michael Gebauer

Epicureans and indeterminism

I think you must be right about Hobbes - at least the indeterminism would be one big difference. The question of whether the swerve can explain freedom is a much-discussed one in Epicurean studies; I think I might mention it in the Lucretius episode. One school of thought is that Epicurus introduced the concept just to explain how atoms become entangled in the first place rather than falling parallel to one another; and then Lucretius invoked it in the free will context. But as I say it's very controversial what theoretical role(s) it was intended to play.

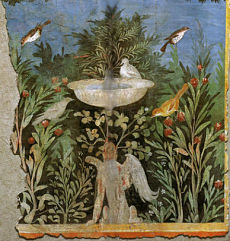

image

Wonderful series...

What is the origin/location/title of the image you use of the garden with birds? I'm researching fresco painting from around this time and would so love to know.

In reply to image by Garden of Livia

Garden

It's not a fresco actually, it is a book manuscript. I lifted this from Wikipedia, to be honest, the entry on "Epicureanism," and the caption there says De rerum natura manuscript, copied by an Augustinian friar for Pope Sixtus IV, c. 1483, after the discovery of an early manuscript in 1417 by the humanist and papal secretary Poggio Bracciolini.

In reply to Garden by Peter Adamson

Images and Swerves

Peter, the manuscript page illustrates your post on Lucretius (58). The beautiful garden scene on this post (55) is indeed a fresco, which features in the Wikipedia article on the Roman Empire (City and Country section). Attribution: Pannello di pittura parietale da area vesuviana, miho museum, shiga 02.jpg. So, 'Vesuvian area' and ending up in a museum in Japan - if only they could talk!

As you mention Poggio, have you read 'The Swerve' by Stephen Greenblatt? I think it's a wonderful tour de force of philosophy, history and biography with, at its heart, an account of the rediscovery in 1417 by Poggio of what was believed to be the last surviving manuscript of Lucretius, and the subsequent explosive impact of its publication on medieval Europe. Greenblatt boldly subtitles his book 'How the Renaissance Began', which upset a lot of historians (see Wikipedia hatchet job), but he makes a strong argument: Epicurean science and ethics disseminating across Christian Europe through an exquisite Latin poem, the immediate literary precursor of the revered Virgil. We learn that Poggio had an extraordinary life, both as a manuscript hunter in remote monasteries and as papal secretary to the Antipope formerly known as John XXIII - a pope adjudged to be so evil that he was stripped of his name and title, and for over 500 years none dared to adopt the name until the controversial reformer Cardinal Roncalli .... Dan Brown couldn't make this stuff up!

In reply to Images and Swerves by Stephen

Swerve

Actually I haven't read The Swerve yet but it is definitely on my list, as I will want to cover the reception of Hellenistic philosophy when I get to the Renaissance. So, a synopsis of Greenblatt is probably coming to the podcast before too long. Thanks for the info on the fresco!

Aristotle Death

The text seems to say that Epicurus was born in 341 b.C. "six years after Aristotle died" which is not correct. Aristotle died in 322 b.C. when Epicurus was already a young man.

In reply to Aristotle Death by Washington Kuhlmann

After Plato

Maybe I misspoke when I did the recording but I just checked the book version and there it says "after Plato died," not "after Aristotle died". (And that date is correct I guess: he died 347.)

your opinion

How good or adequate do you find this lecture on Lucretius?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mXqHOF1B808&feature=youtu.be

THE VOID

Could you please clarify the notion of void? Void is empty space. Is void part of the realm of being or non-being?

If void is part of the realm of non-being, then are we meant to understand that whenever an object moves, by moving into a void, it is turning what had been an area of complete non-being into an area of being? And that is one of the reasons Parmenides said that motion is impossible; it's impossible to go from complete non-being to being?

Is this what Aristotle took the Pre-Socratics to mean by void, hence his rejection of the concept? Would it be correct to say that for Aristotle, the world is continuous and full of being; so whenever an object moves, it moves into a space full of being, pushing aside whatever is already in that space, or making room for itself with whatever is in that space?

How does Epicurus see the notion of void, like the Presocratics (void as non-being) or more like Aristotle (void as not so empty space, full of being)? Epicurus is using sensation as a starting point and later as a check on his ideas. On earth, in our practical experience, can a void ever truly be devoid of all being? If it can't be, isn't Epicurus' notion of void really the same as Aristotle's notion of not so empty space? Or, if Epicurus does hold that void is in fact an area of complete non-being, how does he reconcile that with his sensations? You say for Epicurus, that atoms are not conceptually indivisible, only physically indivisible. Taking that distinction between concepts and the physical, could you say for Epicurus that the void is not non-being physically but non-being conceptually?

In reply to THE VOID by Jdee43

Void and non-being

Those are great questions and I should start my answer by saying that to some extent this is all a matter of scholarly debate: in particular whole books have been written about the extent to which the ancients had a notion of "space" and what that would mean (see for instance Algra, Concepts of Space in Greek Thought). Aristotle's position is fairly clear: void is impossible for a variety of reasons but maybe the most intuitive is that motion is for him (all else being equal) inversely proportional to the density of the medium. So a medium of "zero" resistance, i.e. void, would yield infinite motion which is absurd. As for the Pre-Socratic atomists you're right that they call void "non-being"; this is often seen as a response to Parmenides, so the idea would be that we embrace non-being in our metaphysics, as he refused to do, and being = atoms, non-being = void. But this is puzzling because, can non-being have "regions" or "parts" through which atoms move? Thinking about it from this angle it is useful to remember that Greek for void is "to kenon" meaning literally "the empty." So we're talking about something extended but not full, maybe on the analogy of an empty vessel. This seems to be Epicurus' idea too: and he confirms the reality of void on the grounds of sensation by arguing that our perception of motion shows that void is needed otherwise everything would be totally full and nothing could move. Aristotle, as you rightly say, had already responded to this by saying that things can move around and redistribute to make space for each other; there can also be changes in density, but no emptiness.

Void, Emptiness, and Non-Being

I guess the question boils down to, is emptiness the same as non-being?

I would say no. Emptiness implies a container, a receptacle, boundaries. Can non-being really be contained? Can non-being really be bounded?

Is it fair to say that ideas like void, emptiness, and non-being are fuzzy in ancient philosophy? They weren't fully fleshed out; some of the implications of these ideas not really noticed?

In reply to Void, Emptiness, and Non-Being by Jdee43

Void and non-being

Or maybe it would be better to say that they did work out views on this, but not ones we would find intuitive now. Void and emptiness are kind of the same concept here because the same Greek word means both. This isn't so weird for us conceptually, though. I agree that on the face of it emptiness doesn't sound the same as non-being, but if you imagine you are starting from Parmenides who thought that being is one, and is shaped like a single homogeneous sphere, you could imagine that the atomists could have thought "no, that's wrong - let's split up being into many fundamental things, which would need to be atoms to stop them from being split further." And then whatever separates them would be non-being, which Parmenides did not allow. So the point here is that a spatial arrangement is being equated with metaphysics: all of being together vs all of being disseminated into atoms. We find this odd because we think of "space" as a separate, independent thing, which is why you are saying that emptiness isn't non-being (for us it is empty space); but they don't really have a notion of space like that, it takes many centuries to develop.

Add new comment