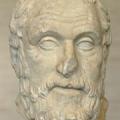

71 - Rhetorical Questions: Cicero

Cicero’s philosophical works are invaluable records of Hellenistic thought. But what kind of philosopher was Cicero himself?

Themes:

For Cicero’s works see the facing-page Latin editions and English translations available in the Loeb series from Harvard University Press.

• J.W. Atkins, The Cambridge Companion to Cicero's Philosophy (Cambridge: 2021).

• J. Glucker, “Cicero’s Philosophical Affiliations,” in J.M. Dillon and A.A. Long (eds), The Question of Eclecticism (Berkeley: 1987), 34-69.

• M. Griffin and J. Barnes (eds), Philosophia Togata: Essays on Philosophy and Roman Society (Oxford: 1989). [See Barnes’ piece for Antiochus of Ascalon.]

• P. MacKendrick, The Philosophical Books of Cicero (London: 1989).

• S. Maso, Cicero's Philosophy (Berlin: 2022).

• J.G.F Powell, Cicero the Philosopher (Oxford: 1995).

• D. Sedley (ed.), The Philosophy of Antiochus (Cambridge: 2012).

• K. Volk, The Roman Republic of Letters: Scholarship, Philosophy, and Politics in the Age of Cicero and Caesar (Princeton: 2022).

• R. Woolf, Cicero: the Philosophy of a Roman Sceptic (London: 2015).

Comments

Ruminations on the Original New School vs. Old School Rivalry

Another excellent podcast! Thanks, Peter.

I'm still trying to grasp what prompted Antiochus to turn so strongly. It sounds like he didn't just say that Philo was being a hypocrite, but, realizing Philo's error, he went so far as to agree with the Stoics. Philo seems coherent because he seems to say, "Well, there's a certain leap of faith involved in any knowledge. Therefore, I'm unsatisfied with the stoics definition of knowledge." To get at his skeptic position it seems one has to figure out on what grounds he is skeptical. Is he equally skeptical about the grounds on which he stands? For example, he trusts his own knowledge that allows him to determine he shouldn't trust knowledge. If they are not the same kinds of knowledge, he might have a point, but if these two kinds of knowledge are the same, then why try trust his own position? Maybe the stoics are right? Was it one the basis of these grounds that Antiochus determined that knowledge is possible?

So, to sum it up in one question, do we know the intellectual basis for Antiochus' stance change? I see the historical cause which could be intellectual too, namely that he felt Socrates and friends took a stance more in line with the stoics. And, Plato probably would slap his head because the skeptics are being like the sophists. Or am I being too critical? (Sorry, that's another question!)

In reply to Ruminations on the Original New School vs. Old School Rivalry by Robert

Antiochus

That's a great question, but like most great questions difficult to answer. I think what really provoked Antiochus about Philo's position was Philo's suggestion that Plato had already been skeptical (so that Philo was effectively appropriating the entire Academic tradition right back to the Big Guy as part of the "New" Academy). But that doesn't explain why Antiochus was so appalled. I suspect that it is because his emphasis was so much on ethical subjects, rather than metaphysics or even epistemology. Because he liked the idea that virtue is sufficient for happiness (which, remember, Cicero also likes), he didn't want an epistemology that prevented him from endorsing this claim emphatically rather than suspending judgment about it, or declaring it merely probable. I guess you could then ask, ok but why was he so keen on the ethical issue, and there I have to say I don't know.

In reply to Antiochus by Peter Adamson

Ah..

Makes sense. I remember that you summed that up. Sounds like he had a strong commitment to virtue.

Thanks again!

In reply to Ruminations on the Original New School vs. Old School Rivalry by Robert

Oh yes, and...

I'm catching up on my Aristotle podcasts (Alas, I say it to my shame, since I'm listening to the skeptics before my Aristotle!) But he had some good thoughts about thought. If I remember correctly, the stoics connect the truth of impressions to the reliability of cognition.

Interestingly during World War II C.S. Lewis was asked to make a speech on the problem of futility by the president of Magdalen College [hope this doesn't bring up a rivalry], and he got into the question of whether or not the universe was futile. He mentioned that we might have a thought that human thought is alien to the way things really are. He points out that this is a contradiction and argues that, "...there is therefore no question of a total skepticism about human thought." And he says: "We are always prevented from accepting total scepticism because it can be formulated only by making a tacit exception in favour of the thought we are thinking at the moment-- just as the man who warns the newcomer 'Don't trust anyone in this office' always expect you to trust him at that moment." The contradiction shows that at least some human thought is not merely human, but truthful, cosmic, or super-cosmic. (Sounds a little like Aristotle?)

So do any, all or which of the skeptics agree that cognition is reliable? (I'm trying to stick with the categories the Greeks use or have I already violated them by my inquiries?)

So, tying it in to the original question, did Antiochus mistakenly approach skepticism as a system and not just the posture of the wise sage? What about Sextus? Do I really have to wait over a week? We'll never make it to Descartes!

tea-towel philosophy

Hey,

One not-very-philosophical question.

I have a tea-towel which has upon it:

"When you have a garden and a library, you have everything you need.... Cicero"

Now, having listened to you all your enlightening podcasts, this strikes me as a very Epicurean sentiment. Yet, I gather also that Cicero had little time for Epicureans, and heaped some scorn upon their collective heads.

So, my question is: is this quote in effect from somewhere where Cicero says "And don't be like those foolish Epicureans who think that...(etc)"?

Do you know?

It actually fills me with glee that I even know enough philosophy to ask this question. (OK, I'm easily pleased. What do you expect? I'm an Epicurean!) I'd be really stoked if you can confirm my hypothesis.

Ta,

Marissa

In reply to tea-towel philosophy by Marissa

Philosophy of tea towels

In reply to Philosophy of tea towels by Peter Adamson

Latin tea towels

That's cool. Thanks for looking it up for me. I think I'll adopt it as a family motto. :)

Marissa

Add new comment